For years, Kory Sheets’ path was illuminated by the bright lights of football stadiums.

When those lights were shut off, the former Saskatchewan Roughriders tailback went to a dark place.

“I went through a stage; I’m actually just coming out of it,” Sheets, 34, said during a recent conversation with The Green Zone’s Jamie Nye. “I was depressed for about five years. I didn’t know which way was up.

“You hear a lot about that mental health thing and I found a therapist. I see her once a week now.”

Sheets firmly believes that getting over the hurdle and opening up to someone may have saved his life.

“That’s a big thing because for a while, I just sat in the house and drank myself to death until I passed out and woke up and did it again just because I didn’t have anything to do,” he admitted. “I didn’t know what I wanted to do.”

After playing NCAA football for the Purdue University Boilermakers, Sheets had NFL stops with the San Francisco 49ers, Miami Dolphins and Carolina Panthers. His pro career took off after he signed with the Roughriders prior to the 2012 CFL season.

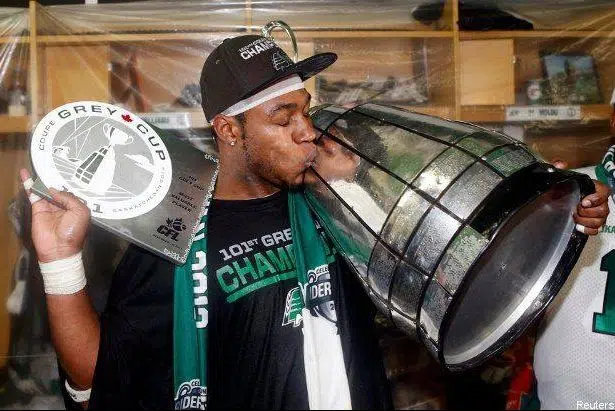

Over the next two regular seasons, he rushed for 2,875 yards and 23 touchdowns. He also was named MVP of the 2013 Grey Cup after rushing for a game-record 197 yards in Saskatchewan’s 45-23 victory over the Hamilton Tiger-Cats.

In February of 2014, Sheets signed with the NFL’s Oakland Raiders. But a torn Achilles tendon suffered in a pre-season game ended his 2014 campaign — and, ultimately, ended his career.

Since then, he said, he has been “trying to figure out life.”

“The way football ended for me, it was just abrupt: ‘Hey, you’re a football player and tomorrow, you’re a regular person. You’ve got to go find a job and pay bills and wonder where your next cheque is coming from,’ ” Sheets said.

“It smacks you in the face. From me talking to the guys, everybody that I know has gone through (a time) where it was like, ‘Man, what do I do?’ And then you fall into that stage.

“You have a regimen (as a player). You wake up to go train, come home, rest, eat and then do film or whatever you’ve got to do and then you take care of the regular part of your life. That’s only maybe five, six hours of the day if you don’t have kids. For me, it was only me, my dog and my lady — and life hit me fast.”

Luckily for Sheets, he was part of a group chat with some of his former Roughriders teammates. They still talk every day, discussing life as much as football.

When he was back in Saskatchewan recently for a speaking engagement, Sheets planned to connect with some of those men to continue those discussions.

“It’s like a close-knit family, a brotherhood,” Sheets said. “It’s different from your actual family, because you all went through things, you all battled together and you saw him (give) blood, sweat and tears just for you. It’s a deeper connection or bond that I feel like we have.”

Sheets also has developed a bond with his therapist, who has helped him deal emotionally with some of the mistakes he made as a younger man.

Those include the legal missteps he took, including domestic violence. That charge was dropped in 2013 after he completed a domestic violence program.

Now, during his public speaking engagements, Sheets tries to educate others in hopes they can avoid the pitfalls he endured.

“When you have the floor, you need to use it at all times,” he said. “When I was up here, I tried to do that. But since I stopped playing, I felt like I didn’t have a voice anymore. In actuality, I do because there are things I’ve gone through that people who are similar to me or people who look up to me have gone through and I could help them. I want to do that.”

He also encourages people to seek help from a mental health professional. He calls his weekly visits to his therapist “the highlight of my week.”

“I don’t know how it is in your community, but in the black community, you don’t talk about your feelings,” Sheets said. “If you hear somebody say they’re going to a therapist, it’s like, ‘Are you crazy? What the hell is wrong with you?’

“It’s not really so much that you’re crazy. It’s that people don’t check on tough people. So every now and again, it’s good to go to somebody and let them sit there (and say), ‘What’s wrong?’ ”

Sheets admitted he stopped watching the CFL after going into what he called “my little hole,” but he has resumed his viewing. He also said he misses Saskatchewan, so his recent visit was something of a tonic.

“It was a close-knit community and I felt like people took me in,” he said. “Actually, they took everybody who was a Rider in as one of their own and and made you feel like family and made it feel like home.

“Coming up here (for this visit), it was like, ‘Hey, I’m going back home.’ ”