Policing our way out of the problem, or taking a proactive, holistic approach?

That’s the question those within the justice system and elected officials are dealing with when it comes to the decriminalization of certain illicit substances. According to a recent report from the Globe and Mail, British Columbia is looking to become the first province to decriminalize carrying small amounts of illicit drugs.

That practice has been recommended in Canada in the past, with studies backing the act of harm reduction in response to the drug crisis.

Scott Bernstein is the director of policy for the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. He joined guest host Mike Couros on Gormley on Feb. 5.

“We need to try different things, and one of the things that is used in many parts of the world and is widely recommended is this idea of not policing our way out of the situation and taking a health-based approach, rather than that of a criminal justice approach to drug use,” he explained.

Bernstein said criminalization creates cases in which users avoid police, hurry injections and do drugs in more ways that are deemed unsafe. That eventually leads to stigma.

“It stands in the way of people going in (and) accessing health care,” he explained, before describing the act as taboo.

Bernstein also said nobody in Canada has died in an overdose situation at a safe consumption site, and if they do overdose, it’s reversed immediately. He explained the issues revolving around decriminalization also create barriers in the way we look at facilities such as the consumption sites.

Bernstein also added decriminalization isn’t the be-all and end-all, but it’s the next step in creating better outcomes for those with addictions.

“It’s not a silver bullet, but the fact that drugs are criminalized really create a lot of these barriers that are standing in the way of other programs, like safe supply succeeding,” he said.

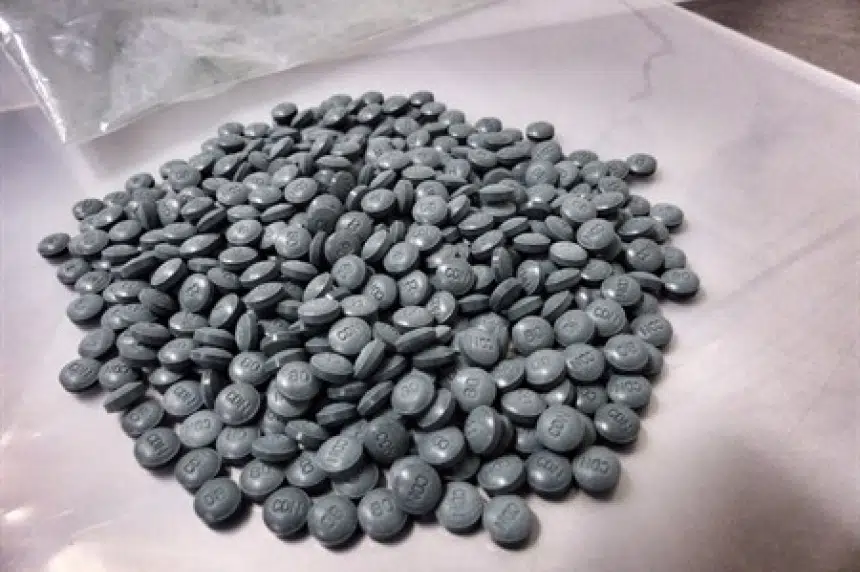

In Saskatchewan, the overdose crisis has risen to heights never before seen. In January alone, 36 suspected drug overdoses caused death in our province. To add to that, preliminary numbers show that 379 confirmed and suspected overdose deaths occurred in the 2020 calendar year. That more than doubled Saskatchewan’s record of 177, set in 2019.

According to the latest report from the Saskatchewan Coroners Service, our province saw more than a death a day due to drug overdose in January.

36 suspected deaths in the month.

That's a pace of 430 + by years end. #Sask's record was set in 2020, with 379 (suspected/conf.)

— Brady Lang (@BradyLangSK) February 4, 2021

So, how close is Saskatchewan to small illicit drug decriminalization?

“I think we’re closer than we’ve ever been to focusing on harm reduction rather than the criminalization of possession of small amounts of street drugs than we’ve ever been,” Saskatchewan criminal defence lawyer Brian Pfefferle said Thursday.

Pfefferle explained now, it’s more of a discretionary call based on the decisions of the Public Prosecution of the Service of Canada in the fall. It made the choice to not charge offenders for most of these types of cases, which has worked in Pfefferle’s eyes.

“We have seen them sticking by that. People are not being charged as often as they were,” he said. “I think that was a very good step, the fact that they’re doing it and the fact that law enforcement appears to be supporting it in some capacity, at least. That demonstrates we’re in a place we’ve never been before in Canada and in Saskatchewan.

“In the last while, there have been discretionary choices made by both police agencies and prosecution offices to not lay charges in certain circumstances.”

Pfefferle added police still lay charges in some circumstances, but if the offenders end up in court, they’re not often pursued with these charges.

The lawyer also cited the recent Good Samaritan Overdose legislation as another good step. It allowed people who may be out on conditions to call in an overdose without fears of prosecution.

“The war on drugs, as we say, is something that never worked. Globally, we’ve seen failures in large centres. Prosecuting production (and) prosecuting sale will still occur; this isn’t giving a free pass to organized crime groups … if we just recognize that making substances illegal has done nothing but drive it underground,” he explained.

“In Saskatchewan, we all know someone … who has lost someone to addiction. It’s a real tragic thing, and we need to appreciate that it can strike anyone at any time.

“These people don’t deserve punishment, typically. They deserve our pity and our support.”

Pfefferle added greater policy works at the ground level, with the focus now shifting to be a health issue as much as it is a criminal issue.

Someone who sees it from the ground level is Jason Mercredi, executive director of Prairie Harm Reduction. His organization is in full support of decriminalization.

“The people who are using drugs aren’t the issue. They have chronic mental health issues. They have homelessness issues,” he explained Thursday, adding decriminalization could also free up police resources.

“Clearly, B.C. is off to the races … I don’t see why we (in Saskatchewan) need to be that far behind them. We’re catching up in terms of health service delivery and/or response to the addictions crisis … especially when we have a record number of overdoses. I think harm (reduction) is going to go a long way for preventing people from dying.”

Mercredi described the war on drugs as an “abysmal failure,” noting chronic mental health issues and those living in poverty are being targeted.

“What (decriminalization) allows us to do is stop focusing on enforcement in policing for your day-to-day user that’s trying to get by, and it’s more looking at it from a mental health lens,” he explained.

“Get them into treatment centres, get them into housing (and) get a case management team around them rather than arresting our way out of this problem.”