On Tuesday morning, the front courtyard of the Muskowekwan Indian Residential School — its doors open less than 30 years earlier — was filled with Indigenous people remembering the children who’d died.

The courtyard was filled with orange: People wearing orange shirts, orange tablecloths, orange T-shirt cutouts waving in the breeze on bushes, and a big sign across the top of the building that read “We support Kamloops.”

The event was put together in just three days to pay tribute to and remember the 215 children whose remains were found in an unmarked grave at a former B.C. residential school, as well as children buried at residential schools across the country.

Half a dozen speakers bared their hearts and, in some cases, their remembrances to the crowd there.

“I was numb when I heard of it. I didn’t know how to articulate how I felt,” Holly Geddes said of when she first found out about the children found in Kamloops. “All of a sudden all the stories my grandmother had told me were true. Three days ago, I realized the horror stories she told me were true.”

Geddes said when her grandmother would talk about the terrible things that happened at school, Geddes would ask her not to talk about that.

“I feel guilty I didn’t believe her,” Geddes said. “I believe her today.”

Geddes is a councillor for the Muskowekwan First Nation and is also a former student at the residential school there. She explained that, in 2018, they found 38 unmarked graves behind the school and it’s believed there are more in the field beyond.

Others shed tears as they spoke.

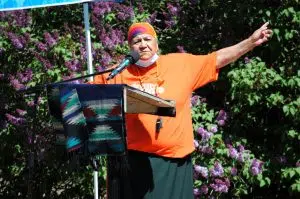

Val Desjarlais speaks to the crowd at a vigil at the former Muskowekwan Indian Residential School on June 1, 2021 (Lisa Schick/980 CJME)

“I want to pay tribute to all the mothers and the grandmothers,” began Val Desjarlais, her voice filled with emotion, “and to the great-grandmothers whose children never came home, whose children were taken from their arms, from their homes, their families, their communities.”

Desjarlais said she got angry when she heard about the children in B.C. and she started thinking about her mother and grandmother, and the children taken.

She asked: “When does justice happen for our people?”

Some of the speakers talked about their time in the schools and the attempts to make them stop speaking their language.

Bill Strongarm, a senator from the Touchwood Tribal Council, said the residential schools destroyed Indigenous peoples’ way of life and language. He explained that language is special.

“Because every word in our Cree language or Saulteaux language has a special and sacred meaning. You dissect a word and it means something special. You don’t get that kind of teaching at the university. You get teachings in that from elders that know the language,” said Strongarm.

Strongarm implored young people to learn their languages.

Strongarm attended the Muskowekwan school and remembered that, at first, he was excited to go to school like his siblings.

“I got a big shock. I was totally surprised at what happened the first day of school. I cried for 30 days for my parents,” said Strongarm.

Lt.-Gov. Russ Mirasty was in attendance and opened his remarks speaking Woodland Cree. He said he appreciates the elders there were speaking and praying in their own languages.

“Given the building that we’re standing in front of, where language was lost, where it was suppressed,” said Mirasty.

Mirasty is a second-generation survivor of residential schools. He said it’s a sad truth that no one actually knows how many graves exist on residential school sites across the country.

“We honour the children by committing to change. And I say we commit to change, that’s all of us. Each and every one of us here, every person in Saskatchewan, every citizen across this country has a role to play in terms of how we come out of this,” Mirasty told the crowd.

The Muskowekwan school shut down in 1997 — one of the last in Canada to do so — and is the last fully intact residential school still standing in Saskatchewan.