On Jan. 11, 1968, the prosecution and defence of Victor Hoffman delivered closing arguments to a jury in a Battleford courtroom.

There was no doubt that Victor Hoffman had committed a horrific crime — the question was whether he had been sane or insane when Jim and Evelyn Peterson along with seven of their children were brutally murdered.

Episode 5 of this podcast series re-enacts the chilling confession Hoffman gave RCMP officers days after the mass murder near Shell Lake.

The episode also reveals how neighbours of the Peterson family narrowly escaped death when Hoffman attempted to stop at their home first — more proof that this crime had been completely and horrifyingly random.

The Shell Lake Massacre podcast is a special presentation by Rawlco Radio. The six-part series hosted and produced by Brittany Caffet airs Tuesdays at 1:30 p.m. on 650 CKOM and 980 CJME. Weekly episodes are available for download on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

Content warning: This episode contains depictions of violence and other content that may be disturbing. Listener discretion is advised.

Listen to Episode 5: The Confession

Listen to Episode 4: The Killer

Listen to Episode 3: The Last of the Petersons

Listen to Episode 2: The Night of Fear

Listen to Episode 1: The Petersons

Transcript of Episode 5: The Confession

Disclaimer: Most of the following transcription is AI generated, and errors may have occurred.

They say there are three sides to every story: Your side, my side, and the truth.

But when one of us is dead, can the truth ever really be known?

We’ll never know with complete certainty what happened in the home of Jim and Evelyn Peterson on that fateful day in August of 1967, but we do have one side of the story.

Days after the family was slaughtered, Victor Ernest Hoffman confessed to committing one of the worst random mass murders in Canadian history. We have that confession.

This is The Shell Lake Massacre. You’re listening to Episode 5: The Confession. I’m your host, Brittany Caffet.

This episode contains audio recreations of written and recorded statements made to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police by Hoffman. The depictions of violence may be disturbing. Listener discretion is advised.

The sun hadn’t yet risen when Victor Hoffman abruptly awoke at three in the morning on Aug. 15, 1967. He got out of bed, got dressed, and then, as the Hoffman farmhouse had no indoor plumbing, he went outside to urinate.

Victor returned to the house and lay on the couch for a while, but he was unsettled. For the next two hours he meandered about the home and yard of his family farm near Leask. He went to the garage and tinkered on an engine he had been fixing, but he tired of the task quite quickly. He saw one of the family dogs in garage and contemplated killing it, but resisted the urge. Instead, he decided to go for a drive.

Victor filled his grey 1950 Plymouth with gasoline from the farm’s fuel tank and drove off, his only companion being the .22-calibre Browning pump-action repeater rifle that he had loaded with bullets before placing it into the front seat.

As he drove off into the dark, he didn’t have a specific destination in mind. He first ventured out onto the highway, then down some back roads, and he eventually found himself back on the blacktop. Once he hit the highway again, he just kept driving, growing closer and closer to the small farming community of Shell Lake. Hoffman described that morning in his confession to police.

[VICTOR: “After it got about daylight, the sun was just starting to come up, I saw that house on the left-hand side of the road, a gate there and I slowed down to it; and I just drove in there and just started shooting there.”]

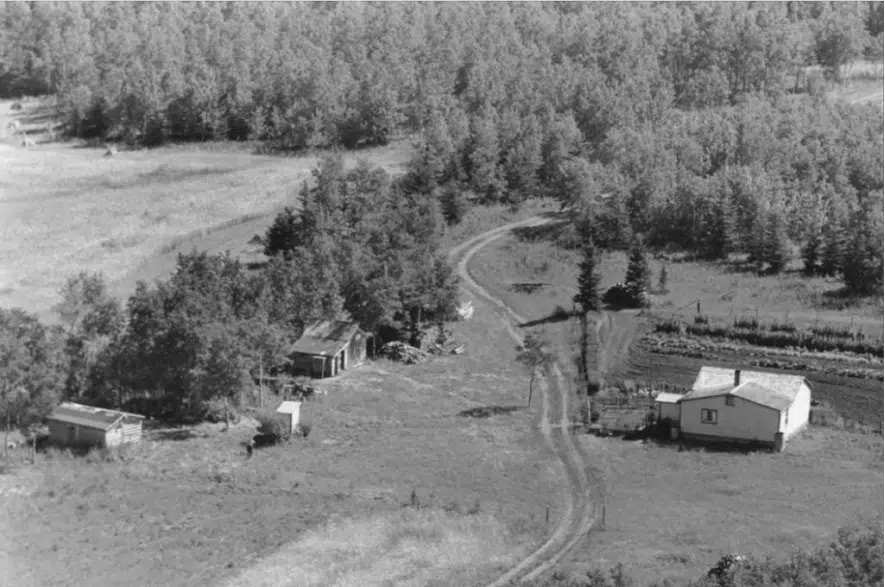

Hoffman drove down the driveway of the Peterson home, stopping to open two closed gates along the dirt road, and brought his car to a stop in front of the small white farmhouse that Jim, Evelyn and eight of their children called home.

He got out of his vehicle, gun in hand. He headed toward the house and opened the unlocked front door. Many of the details that Hoffman included in his confession to police are incredibly graphic and may be difficult to hear. Please listen with care.

[VICTOR: “Walked in the house, this here guy he was sitting on the bed and he says, ‘Who is it?’ And he kept on saying that and when he saw the gun — well, he jumped up on the bed and I shot him. He said, ‘Hey, don’t shoot me. I don’t want to die.’ I shot him. He jumped off the bed and he kept coming at me and grabbing me right by the neck here. He was trying to get me, but he was shot and I kept on shooting him with the gun until it was empty and when I shot the last shell into him, he fell down. He finally hit the floor.”]

Jim Peterson had fought fiercely to defend himself and his family. He had pushed Hoffman almost all the way out of the house, but it hadn’t been enough. He was now on all fours just inside the front door of his own home, dying.

[VICTOR: “My bullets were making him weaker. He almost had me too. I wish he would have. It would have just been attempted murder then.”]

Hoffman went back to his vehicle. He had every opportunity to get back in the car and drive away. Instead, he reloaded his weapon. He went back into the home and shot Jim again, this time killing him. Then, he began slaughtering the children.

[VICTOR: “There was two girls awake. They screamed at me, ‘Don’t shoot me, I don’t want to die. We don’t want to die,’ they said. And they just ducked underneath the covers and I went there and shot them. My head was really spinning. Then because I had already committed murder, I kept on shooting. No sense stopping now.”]

Evelyn, who had been in the bedroom, had climbed out the window with baby Larry in an attempt to escape. Hoffman followed her outside.

[VICTOR: “I heard her come out the window and I went around the other side of the house, around this way, and I think she saw me and she said, ‘Don’t murder me.” I did. I shot her in the chin, she fell down on the ground and I shot her again in the head. She had a baby. I didn’t shoot the baby yet, and I didn’t want to shoot it. So I went back in the house and finished off the rest of the girls. They were still screaming, making funny noises, they weren’t completely dead yet. The bullet in the head just didn’t want to kill them.”]

One by one, Hoffman killed the remaining Peterson children … all but one. He left four-year-old Phyllis alive. He claimed that he let her live because she had been hiding under the covers, hadn’t seen his face and therefore wouldn’t be able to identify him … but that explanation doesn’t make much sense when you consider the fate of one-year-old Larry, who wasn’t even old enough to speak at the time. Hoffman refers to the little boy as “it.”

[VICTOR: “I went back out there at the last and I finished it off. I didn’t want to shoot it, I hated myself for shooting it. I didn’t want it to suffer, I didn’t want to think nobody would find it for three or four days and it would starve.”]

He shot the infant in the head.

Victor spent the next half-hour searching the home and yard for cartridge casings. He knew police would be able to use them to identify the murder weapon and wanted to cover his tracks as best as he could.

He shook out the blankets on the beds containing the mutilated bodies of the Peterson children and covered them back up once he had retrieved the evidence he was looking for.

[VICTOR: “I started collecting them. I collected 17 of them. I counted them right there in the house on the sewing machine. I figured there had to be some more missing and I looked and looked and looked and couldn’t find no more.”

He put the 17 shell casings into the right pocket of his suede jacket, hoping he had found enough to throw police off of his trail. At about 6:30 in the morning, Hoffman got back into his car and drove off, leaving the Peterson farm.

[VICTOR: “I drove home. I felt real sick. I was just thinking I’d have to shoot myself but I didn’t know where to shoot myself where I’d die quick. I saw how they died. They died so hard and they didn’t want to die. I don’t know where my heart is even … it’s here, isn’t it?”]

During the recorded interview Hoffman was asked if he had ever had the urge to do something like this before.

[VICTOR: “No, just those few minutes there; it just popped into my mind, just like that. Do you think I could get rid of it? No, sir; I just went and done it anyway. I don’t know what got into me.”]

Just before the tape recorder was turned off, police asked Hoffman if there was anything else he would like to say. He thought to himself for a moment, and then said quietly:

[VICTOR: “Just that I know that I’m sick in the head and that’s all. But I could never kill again. I know that.”]

We may never know the real truth of what happened within the walls of that small white farmhouse near Shell Lake that morning, but the details of the horror that Victor Ernest Hoffman left in his wake will never be forgotten.

Hoffman had murdered James and Evelyn Peterson and seven of their children on Aug. 15, 1967. On Aug. 19, just hours after his victims were buried, he was arrested without incident by the RCMP at his family’s farm near Leask.

On Aug. 21, Kathy Hill saw the man who had killed nearly her entire family in person for the first and last time. Hoffman appeared in court and was formally charged with capital murder in the death of James Peterson.

[KATHY: “They had a hearing for him in Battleford. And I went to that. Because I wanted to see the guy. And he … he just wasn’t there, like there was something missing. He didn’t think he had done anything. I remember thinking at the time that it’s a good thing my dad wasn’t there because … the guy wouldn’t have made it to a court case. My father would have been the one in jail.”]

In the days that had followed the murder, many conversations in Shell Lake and across the entire nation were full of conjecture about what kind of monster could have possibly committed this horrific massacre.

And here he stood. He was no monster … he was just a man. That realization was a shock to Kathy.

[KATHY: “I just felt like I wanted to see what kind of person would do something like that. And … he was just a plain, ordinary person.”]

This was the only court appearance that Kathy attended. She never saw Hoffman in person again.

After his court appearance, Hoffman was taken to Saskatoon and underwent a psychiatric examination at the University of Saskatchewan. In just a matter of days, he was deemed fit to stand trial.

A two-day preliminary hearing was held at the Court of Queen’s Bench in Battleford on Oct. 24-25, 1967. It was during this hearing that Crown prosecutor Serge Kujawa asked to amend the original charge against Hoffman. He was now facing two counts of non-capital murder in the deaths of James Peterson and Evelyn Peterson. A charge of non-capital murder meant that the death penalty, which would only be abolished in Canada years later in 1976, would not be on the table if Hoffman was found guilty of the crime.

Defence attorney Ted Noble had been appointed to act as counsel for Hoffman. Victor entered a plea of not guilty, and the defence would argue that he was legally insane at the time of the crime and should therefore be found not guilty by reason of insanity.

I asked Lisa Dailey, the executive director of the Treatment Advocacy Center, exactly what not guilty by reason of insanity means.

[LISA DAILEY: “I’m an attorney and basically one of the things that you learn when you’re learning about criminal law is that a criminal act requires two elements. It requires what they call an Actus Reus, which is the bad act — so the thing that you did that would be considered a violation of the law — and Mens Rea, which is the guilty mental state. So that’s where the insanity defence would come in. If you’re saying that a person committed an act, but they didn’t have the the mental state that they would have had to have for you to consider that person to have committed a crime, that is exactly where that determination needs to be made in the legal system in terms of whether somebody is held accountable as somebody who perpetrated a crime, or they need to be treated as somebody who committed an act that would be a crime if they had had the mental state to make them guilty of committing a crime. In Canada at the time of this crime the standard would have been the M’naghten Rule and what that basically means is you could be found not guilty by reason of insanity if at the time you have a mental illness that caused you to act in this way and it had to have been a situation where you either didn’t understand the nature and quality of what you were doing or you were unable to appreciate the criminality of what you were doing.”]

Following the initial two-day hearing, the presiding judge deemed that there was indeed sufficient evidence to put the accused on trial.

On Jan. 8, 1968, the trial of Victor Hoffman opened in the Court of Queen’s Bench in Battleford. A jury of 12 had been selected who would determine Victor’s fate.

By this time, Kathy Hill and her husband Lee had returned to British Columbia, taking Kathy’s four-year-old sister Phyllis with them. They still didn’t have a phone, but Kathy was able to count on family members to keep her up to date on the court proceedings.

[KATHY: “Lee’s mother could call. Like, our neighbour and our landlord had a phone. People could phone there and she would run down and tell me I had a phone call. I think Lee’s dad spent a lot of time at the trials and what have you. So they always knew what was going on.”]

Along with Kathy’s father-in-law, many friends and neighbours of the Peterson family made a point to attend each of Victor Hoffman’s court appearances as well as the trial.

Every single time Hoffman was in court, Marjorie Simonar and her husband Alvin, who had lived right across the highway from the Petersons, were also there. Marjorie still recalls how surprised she felt when she first saw Hoffman in person. His actions against the Petersons had been horrific, but there was nothing about his outward appearance that hinted at the violence he was capable of.

[MARJORIE: “He didn’t look like he’d be a killer. He looked like an ordinary person. He just looked like a regular farmer.”]

Marjorie Simonar, 94, was neighbours with the Petersons in 1967. She whisked four-year-old Phyllis Peterson away from the murder scene and cleaned her up in the hours after the massacre. Photo taken by Brittany Caffet on April 16, 2023.

Throughout the trial, Hoffman sat in the prisoner’s box with a vacant expression on his face. He seemed to show no emotion or remorse as the shocking details of the crime he was accused of were recounted.

Sitting in court and hearing the gruesome details of how her her friends and neighbours had met their death was difficult for Marjorie, but one moment still stands out in her mind to this day — the moment she realized just how close her own family had come to death.

[MARJORIE: “He said the closer he got to this area … he said he was coming around the lake there and he said he had this urge to stop. And he was going a little bit too fast to stop at our place, so he went to the next driveway and went into Petersons.”]

Hoffman had attempted to stop at the Simonar home, but he had been going too fast and had missed the approach. Rather than turning around and heading back to the home where Alvin, Marjorie and their children lay sleeping, he took the next approach and went to the Peterson home instead. It was more proof that this crime had, indeed, been completely, utterly, horrifyingly random.

Ron Shorvoyce, who was a reporter for CFQC at the time, vividly recalls when the only indication of an explanation as to why Hoffman had committed these murders came out, through an outburst in the courtroom.

Ron Shorvoyce, 77, was a young reporter in for CFQC in 1967 and covered the story of the murdered Peterson family in Shell Lake. Photo taken by Brittany Caffet in Regina on Aug. 1, 2023.

[SHORVOYCE: “One part of the scene did throw us all for a loop. While his father testified and was leaving the stand, Hoffman got up and said, ‘Dad, did you get the diamonds?’ or something to that effect. What he meant by that was the devil had promised him a bag of diamonds if he killed the family. We didn’t know that until later, but the RCMP explained that to us.”]

The trial of Victor Ernest Hoffman lasted only four days. Multiple police officers who had been on the scene and later investigated the crime were called to the stand, as well as psychiatrists who had evaluated Hoffman’s mental state, including Dr. Abram Hoffer, whose testimony was vital for the defence. On Jan. 11, 1968, the prosecution and defence delivered their closing arguments and the jury was sent off to determine a verdict.

There was no doubt that Hoffman had committed the crime — the only question was whether he had been sane or insane when Jim and Evelyn Peterson along with seven of their children were brutally murdered.

The jury deliberated for less than 3 1/2 hours before making its decision.

Victor Ernest Hoffman was not guilty by reason of insanity.

Credits

The Shell Lake Massacre is a Rawlco Radio production. The show was researched, written, produced and hosted by Brittany Caffet. Andrew Taylor re-enacted Victor Hoffman’s confession in this episode.

Supervising producers Sarah Mills and Murray Wood. Story consultant Craig Silliphant. Production support by Dallas Doell. Graphic design by Jennifer Losie. Special thanks to Erin McNutt and John Gormley.