In the final episode of Rawlco Radio’s original podcast series, host Brittany Caffet travels to the gravesite of the Peterson family to reflect on the generational impacts of this crime.

The random killing rampage by Victor Hoffman on a Saskatchewan farm in 1967 still stands as one of the worst random mass murders in Canadian history.

While more than five decades have passed, the weight of this tragedy is still felt daily by those left behind.

Jim and Evelyn Peterson never saw their eldest daughter, Kathy, become a mother to four children or how she stepped up to raise her younger sister.

They also missed watching Phyllis, who survived the killing rampage as a four-year-old, grow up, find love and start a family.

When asked if she forgives Victor Hoffman, Kathy replies: “If you don’t, you’ve got that hatred in you all your life, and that just ruins everything. I’m not going to let him spoil my life. He’s taken enough. You’re not taking any more.”

The Shell Lake Massacre podcast is a special presentation by Rawlco Radio. The six-part series is available for download on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

Content warning: This episode contains depictions of violence and other content that may be disturbing. Listener discretion is advised.

Listen to Episode 6: The Aftermath

Listen to Episode 5: The Confession

Listen to Episode 4: The Killer

Listen to Episode 3: The Last of the Petersons

Listen to Episode 2: The Night of Fear

Listen to Episode 1: The Petersons

Remnants of the Peterson family farmhouse near Shell Lake can be seen among overgrown caraganas more than five decades after a horrific mass murder occurred in the home. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Transcript of episode 6: The Aftermath

Disclaimer: Most of the following transcription is AI generated, and errors may have occurred.

On Jan. 11, 1968, Victor Ernest Hoffman was found not guilty by reason of insanity in the murders of James and Evelyn Peterson … but our story doesn’t end there.

It’s been more than five decades since nine people were slaughtered in that small white farmhouse by the highway near Shell Lake, but the weight of this crime is still felt daily by those who were left behind.

This is the Shell Lake Massacre. You’re listening to Episode 6 – The Aftermath

I’m your host, Brittany Caffet.

Throughout the four-day trial, Victor Hoffman had remained emotionless, staring at his feet with a blank expression on his face. When the verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity was read, he had no visible reaction.

As police escorted him out of the courtroom, he slowly shuffled along and asked where they were taking him. The young man, just four days away from his 22nd birthday, didn’t seem to grasp what was happening.

According to the Warrant of Committal After Trial obtained from the Court of King’s Bench in Battleford, Victor was placed under strict custody at the Correctional Centre in Prince Albert while the powers that be determined how and where he should be treated for his mental illness.

Many people in the community were outraged by the verdict. Victor had tried to hide the evidence of his crimes, going as far as shaking out the blankets that had covered the bodies of the dead Peterson children in an attempt to retrieve evidence. How could he possibly have not known what he was doing?

For her paper Schizophrenia, Mass Murder and the Law, Fannie Hoffer Kahan spoke to Jack Clements, foreman of the jury, about the factors that led to the decision to find Hoffman not guilty by reason of insanity.

One of the strongest arguments for the defence was the testimony of psychiatrist Dr. Abram Hoffer. The following is a statement made by Clements and recreated by a voice actor.

[JACK CLEMENTS: “You get the feeling Dr. Hoffer knows what he’s talking about. After the trial there were some jurors who asked some questions, but a little explanation from myself or someone else on the jury seemed to clear it up for them. In layman’s language, Dr. Hoffer told us exactly what he thought about this. For the average person like myself, the only thing we can rely on is the information given to us by somebody like this. He was logical. I can recall when the doctor described the black devil that the boy saw. He made it so clear to every one of us that there wasn’t any fooling about this: He did see this (and) he was compelled by this thing that he saw. The doctor got the message through to us exactly what the boy was thinking, that the boy was driven by something that was real. It was real.”]

Eight days after the court decision, the Government of Saskatchewan issued a statement. Victor would remain in the Prince Albert Correctional Centre under strict 24-hour surveillance while an investigation into the adequacy of the Saskatchewan Hospital in North Battleford was underway.

On Feb. 12, 1968, Saskatchewan’s deputy health minister revealed that the government had determined that the facilities in North Battleford were not equipped to hold Hoffman. Victor was remanded to the Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Penetanguishene, Ont.

Victor was now in secure custody far away from Saskatchewan and Kathy, Lee and Phyllis were in British Columbia … but the effects of this crime still echoed around the community of Shell Lake.

The Simonar family, who had been neighbours of Jim and Evelyn Peterson, stayed in their home right across the highway from that small white farmhouse after the murders. They didn’t have much of a choice — leaving wasn’t an option. Their home, their livelihood, their entire life, really, was entrenched in that land.

Gale Davidson says seeing the Peterson home in the distance day in and day out caused a lot of inner turmoil.

[GALE DAVIDSON: “We’d go to the highway, you could see their house, or even if we’re at the barn we could see their house from our house. And I’d always think, ‘Maybe tomorrow I’ll wake up and they won’t be dead.’ Like honestly, forever I thought that. And it was so unreal. Like you just can’t fathom that a whole family would get murdered. Like it was so surreal and just awful and almost overwhelming that you can’t even fathom that that would happen.”]

Life slowly returned to a regular routine for the Simonar family, but things never felt “normal” again.

[MARJORIE SIMONAR: “It’s not normal, the way you were carefree before. You always have that at the back of your mind, of what can happen. That wasn’t even dreamed of before that.]

[GALE DAVIDSON: “Part of it is, you just carried on though.”]

[MARJORIE SIMONAR: “No, we couldn’t just drop our hands and say, ‘I’m giving up.’ “]

The Simonar family can recall people stopping in at the crime scene in the immediate days and months following the murders. These invasions of privacy went on for years.

[GALE DAVIDSON: “You’d see cars; they’d be slowing down — you know, like they’re observing the Peterson place. You’d see like daily for years, really, people would stop. And they’d come in and they’d stop and ask questions. It was just almost annoying. You’d think, ‘What’s the obsession with a horrific thing like this?’ There was reporters that would stop in, ask questions and just curious people that would go and break into that house. Like those two young guys that stopped in. Dad was so upset with them. They stopped in and they said they’d broken into the house and tore some wallpaper or some little piece of bloody linoleum off of the floor. People are just crazy.”]

Kathy and Lee stayed in B.C. for a handful of years, but returned to the Shell Lake area in 1969 after welcoming their first son, William, who they had named after Kathy’s brother.

Knowledge about the crime was widespread throughout Canada and many people in B.C. had known about Kathy’s history, but when she came back to Saskatchewan, it was as if the floodgates had opened. Everywhere she went, people would bring up the horrific murders of her parents and siblings.

[KATHY: “Coming back here was really hard. There’s too many people that have to talk and it just … I don’t feel comfortable talking to them. I mean, everybody knows. All of them do.”]

Through all of the uncomfortable interactions in the years that followed, Kathy persevered. She was determined to provide a safe, happy life for herself and her children … and she did.

By 1974, Kathy and Lee had welcomed three more children together — Paula, Nelson, and Naomi. They took over Lee’s parents’ farm and raised five children together, including Kathy’s sister Phyllis. They treated her as one of their own to the very best of their ability, and eventually Phyllis even began referring to Kathy and Lee as her mom and dad.

[KATHY: “She came home from school one time — about Grade 2, I think — and she wanted to know if she could call me Mom because it was just too hard to get by in school without … thinking that she didn’t have a mom and dad. And I said, ‘Yeah, go ahead.’ So she did.”]

Kathy and Phyllis didn’t have many in-depth discussions about the deaths of their parents and siblings. Based on the few conversations Kathy can recall, she is confident that Phyllis, although she was only four at the time of the murders, carried memories of what happened that morning.

[KATHY: “She never did really say how much she remembered, but I know she did remember a lot. She did say once that she remembered hearing Dad say, ‘Stay where you are. Don’t come out.’ And everybody listened. That’s really the only thing she ever said.”]

The family led a good life, but many happy moments were tainted with sadness for Kathy. She saw traits in her own children that reminded her of her siblings, and would often find herself wishing that her parents could have lived to know their grandchildren.

[KATHY: “There was one time Paula won an award for a poem she wrote for Remembrance Day. And I remember thinking then that my dad would have loved to have seen that. There was a lot of things that they missed.”]

Jim and Evelyn Peterson didn’t get the chance to see their eldest daughter grow up. They didn’t see her become a mother, step up to raise her younger sister, and raise four beautiful children of her own. They also missed watching Phyllis grow up, become a mother herself, and find love. The list of things that Jim, Evelyn and the seven children who were murdered by Victor Ernest Hoffman missed out on is endless.

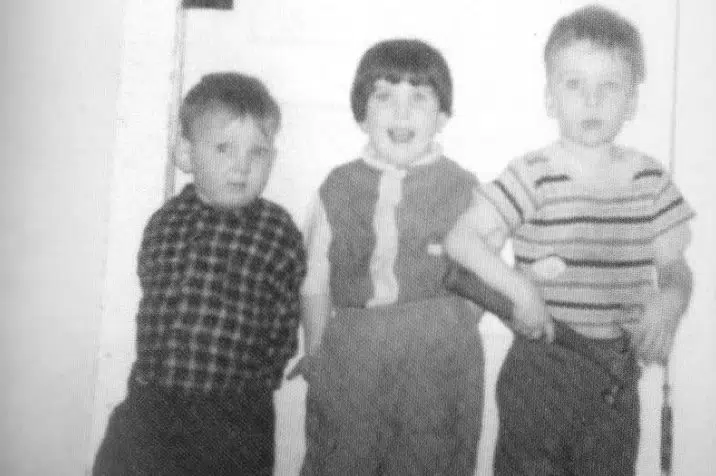

Four-year-old Phyllis Peterson, centre, survived the brutal attack. Police discovered her in bed, nestled between the bloody bodies of her sisters, Jean and Pearl. Photo of siblings from left to right, Colin, Phyllis and William Peterson supplied by Kathy Hill.

As the decades went by, many things changed for Kathy, but one constant reminder of her family’s death remained ever present in her life.

The Peterson home was still standing, and was still regularly being broken into and vandalized. Every few months Kathy would get a call letting her know that someone else had been in the house.

One day in the early 1990s, Kathy’s phone rang. It was a neighbour, alerting her that the small white farmhouse where her family had lived and died was on fire.

[KATHY: “Somebody phoned me telling me the house was on fire. ‘Do you want the fire department there?’ and I said, ‘No, let it go.’ Because there had been a fire go through there once before that took all the out buildings. They fought fire and saved the house and I kept thinking ‘Why? Let it go.’ “]

The house burned to the ground. No one knows exactly what, or who, started the fire, but the destruction of the house was a relief for Kathy. Finally, the crime scene was gone.

On a sunny day earlier this year, Kathy and I visited the Peterson homestead together.

The approach to the farmyard is nearly grown over. If you don’t know what you’re looking for, you would miss the road completely — I’ve driven by it hundreds of times throughout the course of my life and had never noticed it before Kathy directed me to turn in.

As we drove down the narrow dirt path together, she pointed out where the two gates her father had always kept closed previously stood. Dense bush surrounded us on one side, open fields on the other, and I kept my eyes peeled for any sign of the house that had once stood on this property.

As we approached one particularly thick patch of caragana, an invasive shrub, Kathy motioned for me to stop. We got out of the car and precariously made our way through the bush, and then suddenly … there it was. Two concrete steps, the same steps that Victor Ernest Hoffman had made his way up before murdering the Petersons, stood before me in nearly pristine condition.

[KATHY: “Now this is the steps to go into the house and that’s where the house was sitting. This would have been the porch. And then I guess that caragana just took over everything. That’s not a bad thing.”]

Beyond the concrete steps, the crumbling foundation of the house still stands. The outline of the home is larger than I had envisioned, but I imagine that with 11 people inside, it would have felt tiny. A few remnants of the family who once called this crumbling ruined home still remain scattered among the caraganas. Glass bottles, rusted pieces of metal … and the lilac bush that Kathy still remembers planting.

We made our way out of the bush and set off. As we drove away from where the Peterson home once stood, I looked in my rearview mirror. It had seamlessly blended back into the scenery. I’m not sure I could find it again if I tried. After decades of intruders and curious onlookers, the Peterson home finally sits undisturbed.

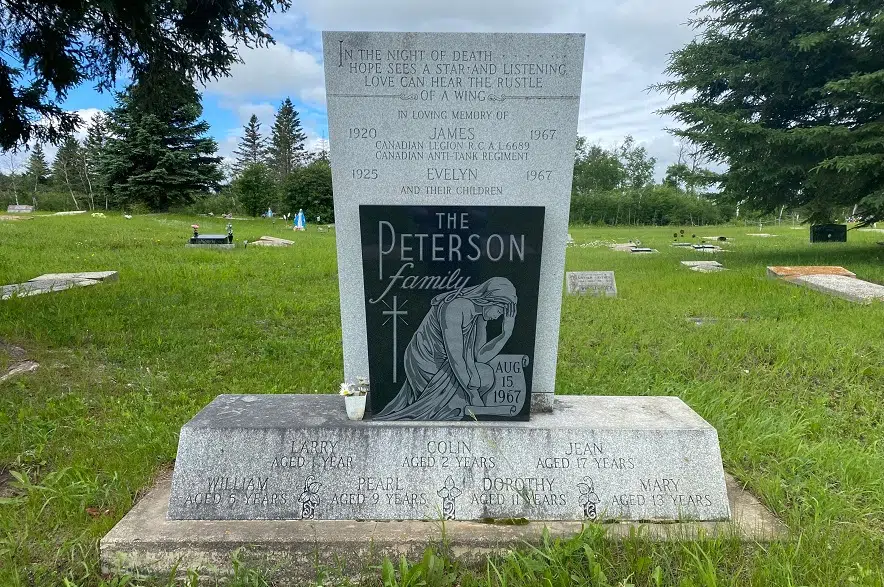

There is another scene tied to this crime that attracts regular visitors — the grave.

Sitting outside the iron gate that encloses the Shell Lake cemetery, you can see the headstone marking the site that holds the bodies of the Peterson family in the distance. It is at least three times bigger than any other marker on the grounds, which Kathy says was for a very sensible reason: They needed a monument big enough to fit all nine names.

The headstone, which was selected and designed by Jim’s mother, Martha, bears a quote from an American writer named Robert Green Ingersoll: “In the night of death, hope sees a star, and listening love can hear the rustle of a wing.”

The gravesite, which should be a place of tranquility, isn’t a location Kathy can bring herself to visit often. It has become a macabre tourist attraction of sorts, something that has caused a lot of pain for Kathy and Phyllis over the years.

[KATHY: “I actually had somebody come and ask me if they couldn’t use that gravesite as a part of Shell Lake’s history and use it in their book for tourists. I said no. ‘Well, it’s part of our history.’ I said, ‘No, it’s not. It’s my history.’ “]

On May 14, 2019, at just 56 years old, Phyllis died after a brave battle against cancer.

In the days and months leading up to her death, she made it clear that she didn’t want to be buried in Shell Lake. The monument for her siblings and parents would be thrust into the spotlight all over again if the sole survivor of the massacre was to be buried there all these years later, and Phyllis wanted no part in it. Her wishes were respected and she was buried in a location that will remain undisclosed.

[KATHY: “She wanted to be somewhere else where it was very quiet, so she went. That’s where she was buried. That’s where she wanted to be, and it is a beautiful place.”]

I’ve been to Phyllis’ final resting place, and I can understand why she chose it. The wind caresses your face as it whistles over the wide-open prairie and wildflowers grow in abundance. Phyllis Peterson, the sole survivor of the Shell Lake Massacre, is now surrounded by a calm, quiet, peace. Just like she wanted.

Kathy Hill shares intimate details of her family’s murder with producer and relative Brittany Caffet on April 6, 2023.

More than 56 years have passed since Jim and Evelyn Peterson and seven of their children were murdered in their own home by Victor Ernest Hoffman on Aug. 15, 1967. Kathy, who is now the only surviving member of the Peterson family, is very much aware that their family was not the only one impacted greatly by this crime. She feels a deep sense of sympathy for the family of Victor Hoffman.

[KATHY: “Nobody cared about them. No, everybody felt sorry for our family, but nobody felt sorry for them. And they were portrayed as a poor old family that didn’t know anything, and that really wasn’t true. You don’t know what your kids are going to turn out like. You have no idea what’s going to happen eventually. All you can do is the best you can and hope for the best.”]

Kathy doesn’t blame Robert and Stella Hoffman for the actions of their son; she blames the system. Victor had been receiving treatment for his mental illness at the Saskatchewan Hospital in North Battleford, but had been released less than three weeks before committing the horrific crime that robbed her of nearly her entire family.

[KATHY: “It was the government of the day that screwed things up. They were releasing people from these mental hospitals long before it was time to let them go. And then they didn’t tell the family how to look after them when they did let them out. So you can’t blame their family. They had nothing to do with it. They had taken him into Battleford and put him in the hospital … (and the hospital) let him back out.”]

Following the trial, Victor was remanded to the Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Penetanguishene, Ont. He stayed within the walls of that facility until the early 1990s, when Kathy and her family were shocked to learn that Hoffman had been granted day passes to leave the facility under supervision.

[KATHY: “What really bothered me though was the fact that the system released him out to the public. Like, why would you do that? You know he’s not well and you’re allowing him back out in the public to do something to somebody else? That was what really bothered me more than anything I think.”]

Thankfully, Hoffman never harmed another family. He died in custody on May 21, 2004.

Kathy Hill now leads a quiet life in the community of Spiritwood, roughly a 20-minute drive from the Peterson farm. Her husband Lee, who was a source of stability and strength for her through the loss of her parents and siblings, passed away in 2007. She is very close with her children and grandchildren and takes great pride in their accomplishments.

Jim and Evelyn, who valued family and hard work above all else, would be proud of the woman their daughter turned out to be.

On a warm, sunny day Kathy and I sat at a table in the kitchen of her home discussing her family and all of the things she has lost. As she shared memories of her family and wondered who they may have become, I asked a question that I honestly wasn’t sure how she would answer.

Has she been able to forgive Victor Hoffman?

[KATHY: “I mean, if you don’t, you’ve got that hatred in you all your life, and that just ruins everything. I’m not going to let him spoil my life. He’s taken enough. You’re not taking any more.”]

Credits

The Shell Lake Massacre is a Rawlco Radio production. The show was researched, written, produced and hosted by Brittany Caffet.

Supervising producers Sarah Mills and Murray Wood. Story consultant Craig Silliphant. Production support by Dallas Doell. Graphic design by Jennifer Losie. Special thanks to Erin McNutt and John Gormley.