On Tuesday morning, the inquest into the killings on the James Smith Cree Nation and in Weldon broke for jury deliberations.

The last of the witnesses finished giving evidence on Monday afternoon, so on Tuesday, the presiding coroner, Blaine Beaven, give the six jury members their instructions.

He said they’d been an attentive jury and were obviously engaged in the process and have been considering the evidence.

READ MORE:

- Day 1: Jury selection, first witness at James Smith Cree Nation inquest

- Day 2: Emotions intensify as testimony continues at JSCN inquest

- Day 3: RCMP witness at JSCN inquest discusses drug trade, warrants

- Day 4: RCMP witness apologizes to veteran’s family at JSCN inquest

- Day 5: Psychologist shares assessment of Myles Sanderson at JSCN inquest

- Day 6: Inquest hears Sanderson wasn’t among Sask.’s most wanted before attacks

- Day 7: Sanderson’s release from custody scrutinized at JSCN inquiry

- Day 8: Parole officers, program facilitator detail Sanderson’s progress in prison

- Day 9: Psychologist offers apologies to families during JSCN inquest

- Day 10: Pathologist tells inquest EMS likely couldn’t have saved murder victims

- Day 11: Elders describe dealings with Sanderson in prison

Beaven gave specific instructions on the evidence, telling the jurors to deal with what was in front of them and to not rely on what a reporter or interviewee might say about the evidence.

He talked about the reliability of evidence and how the jury should choose to weigh it, saying there shouldn’t be many issues with reliability of the evidence. He noted the exception of one case when a witness gave evidence which Beaven said she obviously believed to be true, but the RCMP went back to investigate and could find nothing to support what she was saying.

Beaven also spoke about hearsay evidence, which in an inquest it is admissible, and he gave an example: Staff Sgt. Robin Zentner gave the RCMP presentation explaining the timeline and details of the attacks. Beaven said it gave good information on what happened in the homes without retraumatizing the people who endured it.

The presiding coroner told the jury members they didn’t have to come to unanimous decisions, just majority, and not the same majority was necessary in every case.

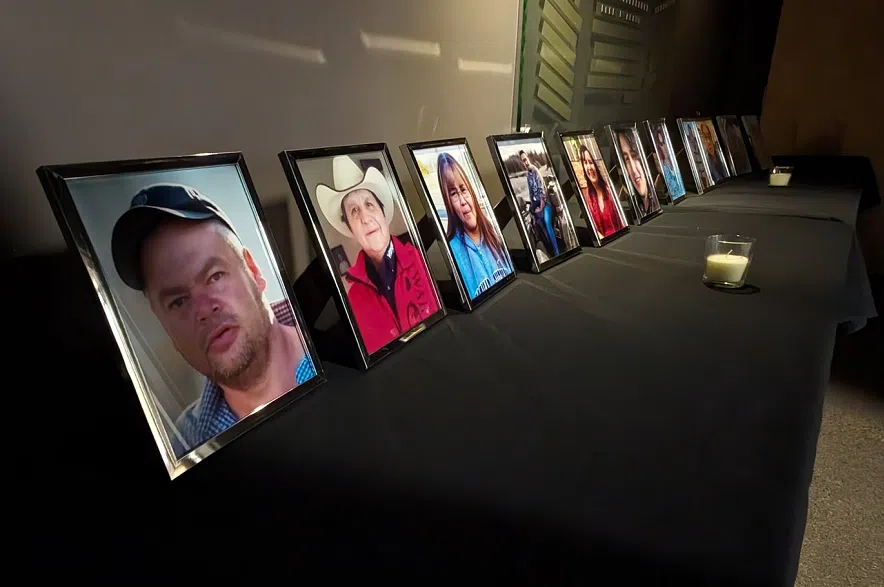

The jurors have to make the official designation for the 11 victims’ names, dates, times, places, causes of death and by what means they died. From the evidence of the two pathologists who gave evidence on the autopsies, Beaven suggested to the jury the answers to those questions for each of the victims.

The jury also has to come up with some recommendations on how to stop the this kind of thing from happening again.

Beaven explained the recommendations need to be practical and lawful and could actually be implemented, and should be based on the evidence that was given in the inquest.

He said they could come up with as many or as few recommendations as they felt necessary.

“You can also make no recommendations if you do not believe there are any to be made. However, it is your duty to try and take this tragic event and make something positive from it to prevent similar deaths in the future, and I urge that you make an honest attempt to do so,” said Beaven to the jury.

Once the jury is done and the recommendations are finalized, they’ll be taken by the coroner’s service and forwarded to those to whom the recommendations were made, such as the RCMP or the Correctional Service Canada.

The coroner’s service will then check back periodically to see how the institution is doing on the recommendations, according to Beaven. However, recommendations coming out of a coroner’s inquest are not mandatory.