100 years ago in 1924, Saskatchewan was booming.

It had the third-largest population amongst the provinces, farms were becoming mechanized and

airplanes started to appear in our skies.

And the prohibition on alcohol in the province was voted down.

The Dry Days

When you think of prohibition, you’re likely picturing gangsters, Tommy guns and barrells full of illegal

booze being smuggled through secret tunnels.

City of Saskatoon archivist Jeff O’Brien says that wasn’t exactly the case here in Saskatchewan.

In 1915, Saskatchewan held a prohibition plebiscite, and voted to “ban the bars”.

But it wasn’t quite the dry picture many of us have been envisioning.

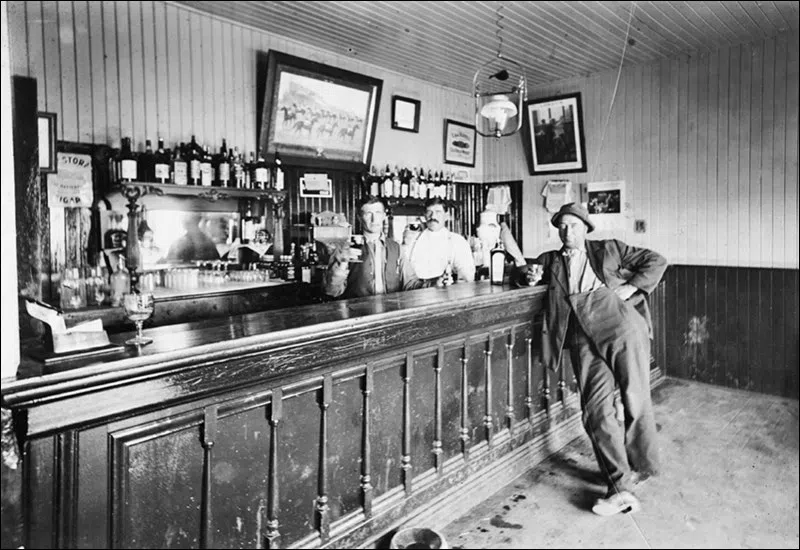

Bars and beer parlours looked very different pre-1920s in Saskatchewan. There were many rules you had to abide by to even get inside and enjoy a drink. (Glenbow Archives, NA-3853-23)

“It doesn’t mean that they padlocked the bars. It means that the bars can’t sell alcohol, right? They pull

all the liquor licenses,” explains O’Brien. “So a bar can’t sell alcohol, and all the private liquor stores

were also closed, but the government immediately turns around and opens government-run liquor

stores.”

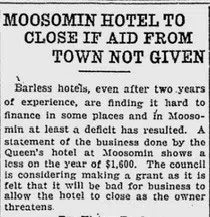

At the time, in order to have a liquor license in Saskatchewan, you had to serve meals and offer rooms.

So essentially, a hotel. But often the bar was the only part that made money, which left business owners

with few options for their struggling businesses.

“There’s a wave of mysterious hotel fires in rural Saskatchewan right after July 1st,1915, because the

owners in the small towns are going, “I can’t afford to run my business,” so they burned the hotel

down”, says O’Brien.

Many hotels and businesses were forced to closed due to decreasing revenue during prohibition in Saskatchewan

(Regina Leader-Post, October 28 1918)

The bars did try to make a go of selling other items, including light beer, ice cream, and soda. But

Saskatchewan residents only wanted hard liquor or strong beer.

In Saskatoon, there were many raids on establishments that frequently broke the rules.

“The big culprits in Saskatoon were the Albany and the Berry, the Queens, and the Windsor,” O’Brien recalls. “So (those were) the four bad boys of Saskatoon’s liquor trade. They were continually getting caught with alcohol in the drink cooler, and selling alcohol under the table. The owner of the Queen’s Hotel once got arrested for selling alcohol out of a booth at the exhibition!”

O’Brien says there were other ways you could get booze, including by prescription.

In fact, during the influenza epidemic in 1918, drugists were allowed to sell alcohol without a prescription, because it was felt to be a possible preventative for influenza.

The streets of Saskatchewan looked very different than how they do today. (Moose Jaw Public Library Archives)

CANADIAN BOOTLEGGERS

With a much stricter prohibition down south, Americans looked to their Canadian counterparts to

smuggle in the hooch.

“A lot of bootleggers in Saskatchewan were, like the little Ukrainian Baba, you know, next door, who

was making bathtub gin or brewing beer,” describes O’Brien.

“But there were some major alcohol liquor dealers, and people talk about the Bronfman family. The

Bronfman’s family made their money selling alcohol to the states, because see, in America, alcohol was

forbidden. So all liquor sales were illegal, and they looked to Canada to supply them with a lot of their

alcohol. And so the Bronfman family made a killing selling alcohol into the States.”

THE GREAT WAR

The start of the First World War is what truly made Saskatchewan dry.

“The Ban the Bar pitch was pitched as a way to support our boys overseas,” explains O’Brien. “The

First World War is going on, and you know, it’s unpatriotic to waste your money spending it on alcohol

when you should be supporting the soldiers in the trenches.”

But even the Canadian soldiers weren’t going without alcohol in 1918.

“Canadian soldiers, like the British soldiers, got their tot of rum every day, unless they refused it, in

which case they got extra tea,” O’Brien says.

In 1918, the federal government shut down the liquor trade under the War Message Act.

And so Canada then did become truly dry.

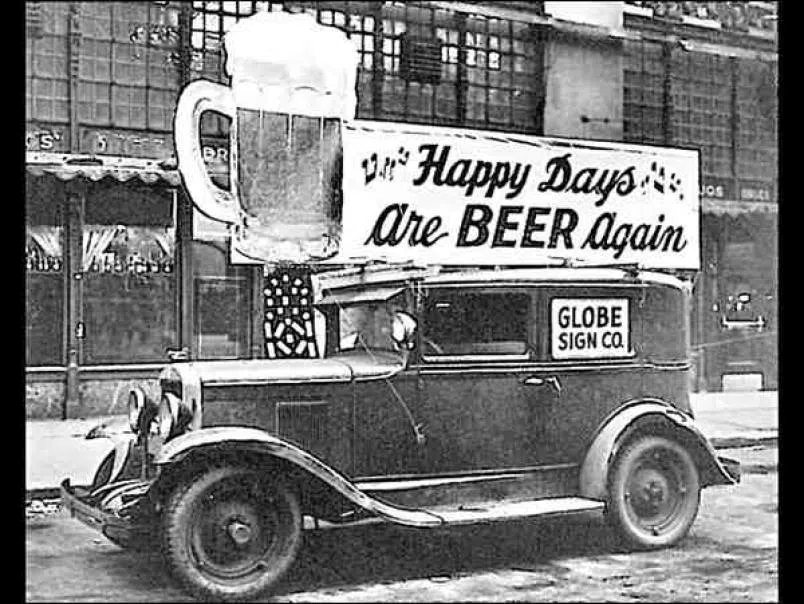

THE END OF PROHIBITION

In 1924, another plebiscite was held to decide whether or not to allow the sale of alcohol in

Saskatchewan.

A public vote was held on July 16th, 1924, to find out if residents were in favour of prohibition, and if they

wanted to allow alcohol for purchase in stores, as well as in bars.

By a very small margin, Saskatchewan voted to open the liquor stores, but not to open the bars.

The beer parlours would not open until 1935.

With liquor stores back open, prohibition in Saskatchewan came to an end, at least on paper.

“Is it fair to say that that plebiscite in ’24, was the first step toward the end of prohibition? I mean,

it was the end of prohibition because we can now sell liquor, right?” O’Brien rationalizes.

“Prior to that, in Saskatchewan from 1918 to 1924, you couldn’t sell liquor. You could still buy it by mail, and

you could still get it by prescription, but you couldn’t sell it in a liquor store. So I think you could

legitimately say that the prohibition ends in 1924.”

So while it’s not the dramatic bootlegging and Tommy Guns story that many imagine, the end of

prohibition in Saskatchewan is still a tale worth raising a glass to.