Not with a bang, but a whisper

Retired University of Regina journalism instructor and filmmaker Layton Burton vividly remembers visiting his father in the hospital during his final days in 1993.

“He must have understood that he wasn’t going to get out of this alive. I remember being in the hospital room with him, and he put his hand up and I walked over to him, and he grabbed me and he said, ‘I’m not who you think I am’,” Burton recalled. “I thought it might have been the brain cancer clouding his thoughts. And he pulled me in tighter and said the same thing, ‘I’m not who you think I am’. And then he sort of drifted away. What does that mean?”

Jack Burton, 72-years-old at the time, was battling brain cancer. But there was another battle raging inside of him. One between the identity he had been assuming his entire life — and his true self.

After these words and this visit, Jack passed away the following morning. It was when Layton returned to his mother’s home that a neighbour called the house.

“She said, ‘Layton, I just heard about your dad.’ and I said, Yeah, he passed this morning. And she said, ‘Was it AIDS?’” Layton was still exasperated, while reliving this conversation.

“I said, What? ‘Was it AIDS?’ No, it was brain cancer. AIDS?! I don’t understand. And she said, ‘Oh, never mind’, and she hung up.”

Between Jack’s cryptic final words and this weird conversation with a neighbour, the cogs in Layton’s head began to turn.

He started to go through his father’s things, trying to figure out what his parting words really meant.

“I found apologetic letters to my mother about the whole situation. I found pictures, I found magazines, I found all kinds of things, that finally, it was an epiphany,” Layton said. “It was that light going on, oh my god, I think he was queer. That’s what he was trying to tell me. That’s when the journey really truly began.”

Who were Jack and Lou Burton?

Jack Burton was the son of a hardware store owner and mayor of Fairlight, Saskatchewan.

He joined the navy as a young man, and served for Canada in the Second World War.

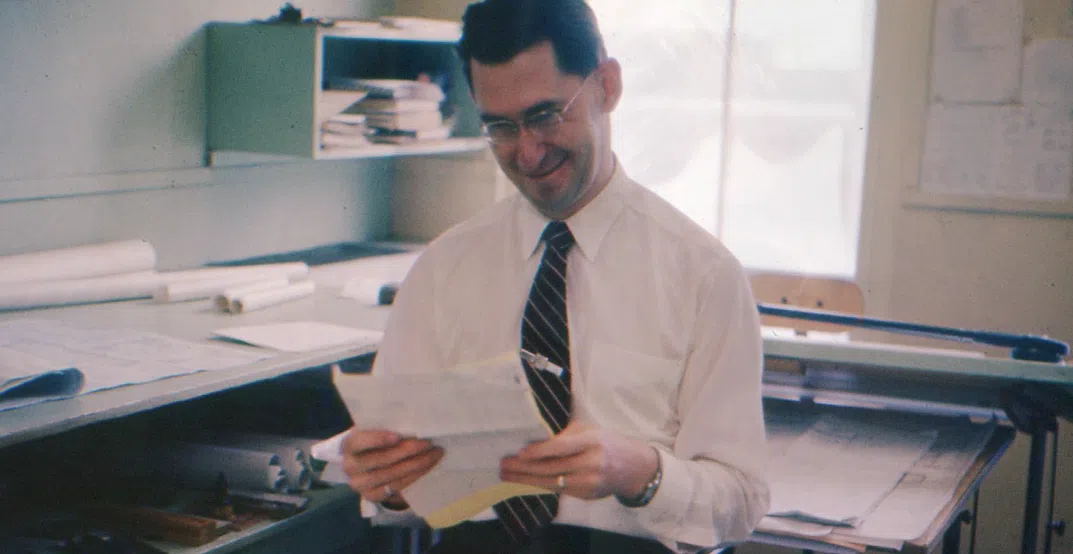

He went to the University of Manitoba and got his degree in architecture. Upon graduation, he was hired as a draftsman at BLM Architects in Regina. He drafted for two years and was made a partner in 1952.

He married Lou that same year.

Ludvina “Lou” Mueller born in 1921, was the daughter of a poor farmer near Cudworth, Saskatchewan. Growing up in the ‘30s, Layton said she was a sickly kid, who had rheumatic fever and heart damage. She was never able to complete school.

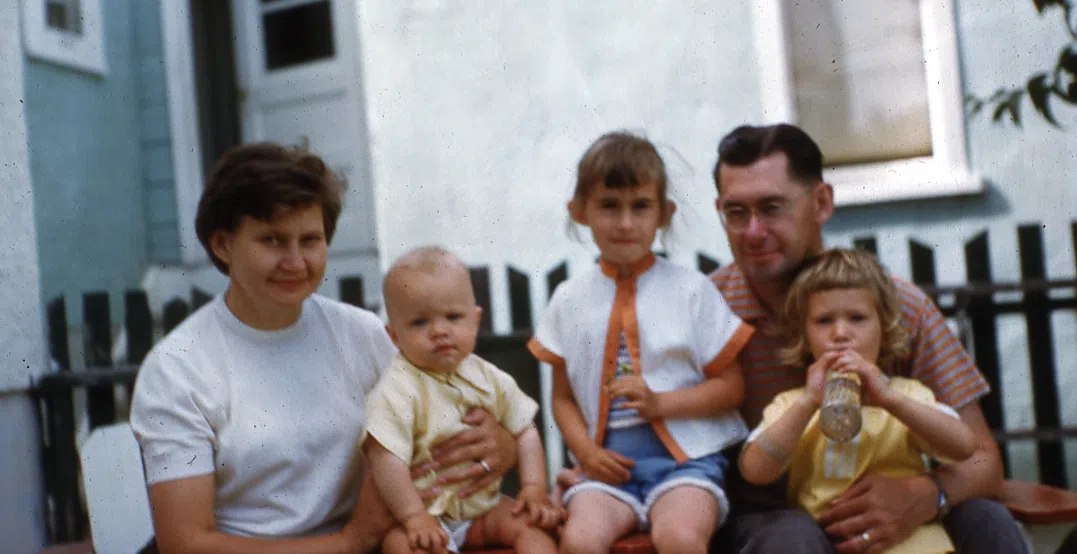

Lou Burton and her three children, raising her family in northwest Regina. (Submitted/Layton Burton)

Jack and Lou met in 1951 at a bowling party in Regina.

“My dad went to my mom and started chatting with her. I think that he got the idea that if he wanted to survive in Saskatchewan as a queer person, he needed to hide, and he needed a cover,” Layton said. “And my mom, who had no advantages in life, no education, no money… I think she saw somebody who was smart, who had a plan, and somebody that she could lean on for the rest of her life to give her a place in the world. I think that’s where their collusion came to be. They decided that they could make this work.”

“She would be happy. He would get what he wanted, and that was a place to hide and a family.”

A year after meeting at that bowling alley, Jack and Lou were married.

They welcomed two daughters, and Layton was adopted in 1961.

Lou, Layton, Layton’s older sisters, and Jack Burton pose for a family photo in the 1960s. (Submitted/Layton Burton)

Layton said he believes Jack and Lou would have had a conversation about his sexuality before they were married.

“My dad was a very honest human being. He would never try and deceive anyone for any reason. He had to have told her,” explained Layton. “My mother was a very matter-of-fact person who could not stand a lie. I think that they compromised from the beginning. I think they realized that they were saving each other, in a sense.”

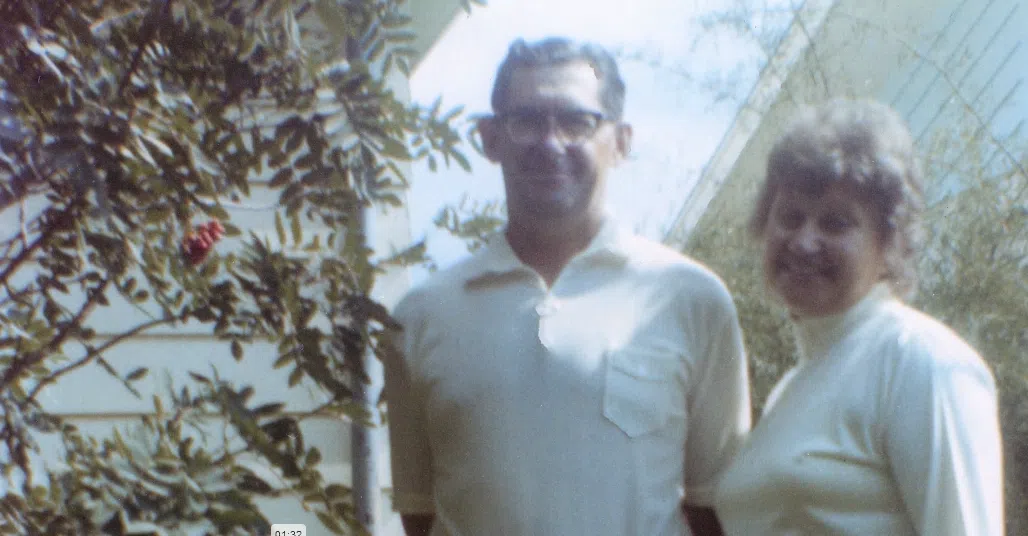

But for as long as Layton can remember, his parents always slept in separate beds.

“I don’t ever remember them in one bed. I look back now and it’s funny. I had lots of friends in my neighborhood but one in particular, I remember him coming into our house one day and for some reason we ended up in my parents’ bedroom and he goes, “So what’s the deal with the two beds?” And again, I never thought about it because it was always like that,” Layton recalled. “I thought about his parents, and I’d been in his parents’ bedroom and I realized, oh, that is odd.”

For as long as Layton Burton can remember, his parents always slept in separate beds. (Submitted/Layton Burton)

Layton said he remembers asking his parents about the sleeping arrangements that night at supper. He was told the separate beds were due to Jack being a light sleeper.

“I’m sure (that is) absolutely not true, but I bought it, and that’s just how I explained it for the rest of my life,” said Layton. “ I think that when you are a married couple, when you are in love, that separation over 42 years can take its toll. And I think it did.”

Layton explores this memory in his short film, “Separate Beds.”

Separate Beds from Layton Burton DOP on Vimeo.

Turning pain into art

After confirming his suspicions with his mother, Layton spent years coming to terms with his father’s most guarded secret.

This revelation, coupled with the slow-down of Saskatchewan’s film industry in 2014, led Layton to reinvent himself.

He headed back to school, to get his film degree at the U of R, taking the pain he felt and turning it into art.

“I was taking fourth-year gender study and sexuality classes with Dr. Claire Carter. I told her my story and finals were coming up, she said instead of an essay, ‘I want you to make a film about your dad and your mom.’ And I said, I guess that would be better than an essay ’cause I’m no good at those,” said Layton.

“And so, I made the film,” Layton said.

He created a short film called “Separate Beds” in 2017, examining his parents relationship from the prospective of their adopted son.

Layton said in making the film, he never realized what a touchstone it would become for his relationship with his dad.

“It was at times overwhelming, ’cause holy smokes, lots to think about,” he laughed. “But it was also a great and cathartic exercise for me to put myself through. You know, I still can’t watch it.”

It’s been seven years since Layton made the film, and he’s filled those seven years with 2SLGBTQ+ advocacy, education, and trying to honour his father’s legacy.

“I didn’t want my father’s legacy, his memory, to be forgotten. I didn’t want him just to be another queer guy who hid his whole life, and didn’t get to live who he was,” Layton explained.

Through this journey, Layton feels his father’s story has helped him to be a better educator for his own students.

“I know that I have affected change in my own classes, for those students who are queer, who are trans, who are non-binary, who are two-spirit. And if that’s my only legacy, that’s enough.”

Lasting legacy

As for his father’s legacy, Jack’s queer identity is only but a fraction of who he really was.

“It’s gonna be 31 years at the end of next month that he passed away, and I found out. He was just a dad to me. I never ever once looked at him in any way, shape or form, thinking ‘my dad’s queer’ or ‘my dad isn’t what the other dads are.’ Not once. It never dawned on me,” said Layton.

“I looked at him as Jack. My dad, the architect, the photographer, the music lover, the guy who, you know, made my world so good, and who inspired me to be who I am today,” continued Layton.

“I can spend my time now trying to flesh out his legacy, and being an ally for all the other Jack’s.”

2SLGBTQ+ seniors study

A University of Saskatchewan and Queer Seniors of Saskatchewan study from May 2023 took a closer look at 2SLGBTQ+ seniors in Saskatchewan, highlighting many of the struggles queer folks face in the province.

The study estimates that around 165,000 2SLGBTQ+ Canadians were over 55 in 2018.

A survey was given to 111 people over the age of 55 who were part of the 2SLGBTQ+ community, with 26 questions focused on coming out and feeling accepted; service access and delivery; discrimination and exclusion; housing and employment; and relationships, family and community.

Most of those polled faced discrimination, with 72 per cent having been discriminated against due to their age. Some 63 per cent said they experienced discrimination due to being part of the 2SLGBTQ community.

More than half of the respondents felt they wouldn’t be able to find an assisted living or long-term care home that would be accepting of 2SLGBTQ people.