If you’ve ever wanted to take in classical art of Roman charioteers and Greek gods, you don’t have to spend thousands of dollars flying to Europe and touring the Pantheon.

In fact, you can immerse yourself in the ancient world right here in your own province, at the University of Saskatchewan’s Museum of Antiquities.

In the beginning…

The museum started as a project in 1974 by ancient history professor Michael Swan and art history professor Nicholas Gyenes at the University of Saskatchewan.

“They thought ‘Wouldn’t it be great if we had a study collection of ancient Greek and Roman art here in Saskatoon?’” explained Tracene Harvey, the museum’s director and curator.

“The only way to achieve that is through full-scale plaster casts or resin replicas, which come from various workshops around the world.”

Tracene Harvey has been with the Museum of Antiquities for 17 years, now serving as the director and curator. (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

The collection began as a dozen replicas purchased from the Louvre in Paris, which were kept in various locations across campus.

In 1981, the collection was officially opened as the Museum of Antiquities after space was found in the Murray Building.

In 2005, the museum was moved to its current location in the Peter McKinnon Building.

Listen to Harvey on Behind the Headlines:

Thanks to private benefactors and the university, the collection has grown to include a lot more than just replicas.

“We gradually expanded into the realm of original artifacts,” Harvey said proudly.

“We have, for instance, a 4,000-year-old false door from an Egyptian tomb, and we have the largest collection of ancient glass in Western Canada. We have a growing collection of ancient medieval coins, and also pottery.”

One of the museum’s original artifacts, a 4,000-year-old false door from an Egyptian tomb. (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

The collection of replicas has expanded to include pieces from the Louvre, the British Museum, the Museum of Antiquities in Delphi, the Acropolis Museum in Athens, the Staatlichen Museen in Berlin, and replicas made by local artists.

Harvey explained that most of the 160 ancient sculptures the museum has are replicas created from moulds taken directly from the original pieces.

She said the collection covers Greece, Rome, and the ancient Aegean cultures such as the Minoans and the Cycladic peoples. There are also pieces representing various ancient cultures from the Middle East, Mesopotamia, Babylon, Persia, Syria and Medieval Europe.

Replicas and originals

The history of the Roman Empire, which spans hundreds of years and multiple continents, is chronicled in the statues and monuments its citizens left behind.

However, Roman art owes a significant amount to the Greeks.

READ MORE:

- U of S Greystone Singers to make Carnegie Hall debut

- Busy, stressful time for families as U of S students move in

- New safety measures at U of S after man with voyeurism history charged again

Although the Romans conquered the Greeks in battle in 146 B.C., the victory was not accompanied by cultural submission.

Instead, Romans clamored for reproductions of famed marble sculptures by skilled Greek artists like Praxiteles.

Many of the examples of Greek art that we have today survive thanks to the Romans crafting replicas of original pieces. (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

“This is a tradition that goes back literally thousands of years,” Harvey said. “A lot of the Greek art that we have that survives to us today is thanks, in large part, to the Romans copying Greek art, because they loved it so much.”

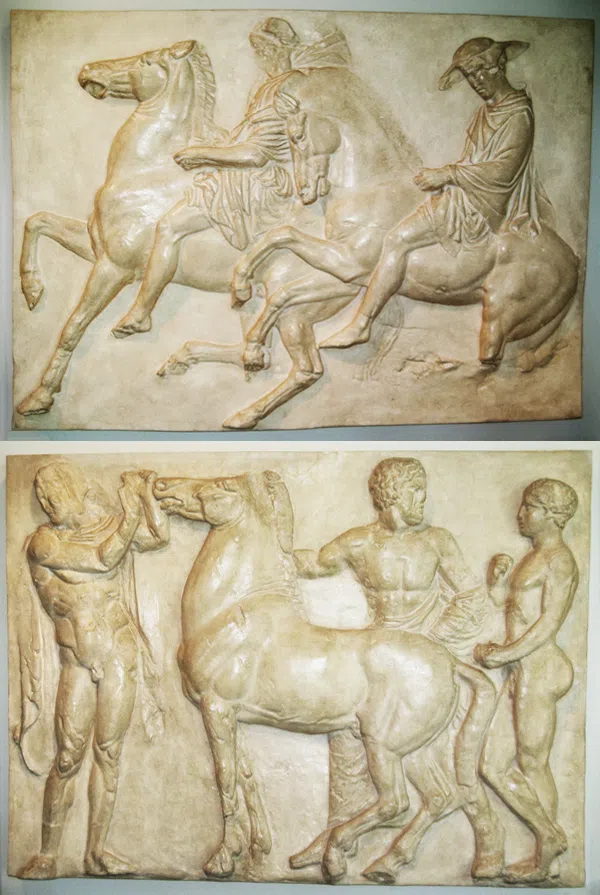

Saskatoon’s Museum of Antiquities is home to two replica panels from the Parthenon Frieze, part of the Parthenon temple in Athens.

The molds for the panels were made in the early 1800s by French archaeologists.

The originals stayed up on the temple until about 20 years ago, when the Acropolis Museum started systematically taking down the original sculptures from the Parthenon and putting them into the museum in Athens.

Panels from the west frieze of the Parthenon depicting part of the Panathenaic procession held in honour of Athena every four years. (Museum of Antiquities website)

Harvey has been to Athens several times over the years, and visited the museum to find the two panels that the U of S replicas are based on.

“The originals have been damaged due to pollution being up on the temple, but our replicas, the molds taken back in the 1800s, are actually better prototypes of the original than the originals,” Harvey explained.

“It’s a tradition that’s important, and we’re proud to be part of that longstanding tradition of preserving art.”

The museum’s current collection

The Museum of Antiquities is located in the Peter MacKinnon Building on the University of Saskatchewan campus in room 106. (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

According to the museum’s website, the institution’s long-term goal is to offer a reliable and critical account of the artistic accomplishments of major Western and Middle Eastern civilizations from approximately 3000 B.C. to 1500 A.D.

“The mandate of the museum is that the replicas have to be precise to the originals, and painted to look as close as possible to the originals,” Harvey elaborated.

One of the most recognizable statues in the museum is its replica of the Venus de Milo.

Originally carved from marble in Greece during the Hellenistic Period, its exact dating is uncertain, but experts say it could be from the Second Century B.C., perhaps between 160 and 110 B.C.

The museum is home to 3D printed replicas as well.

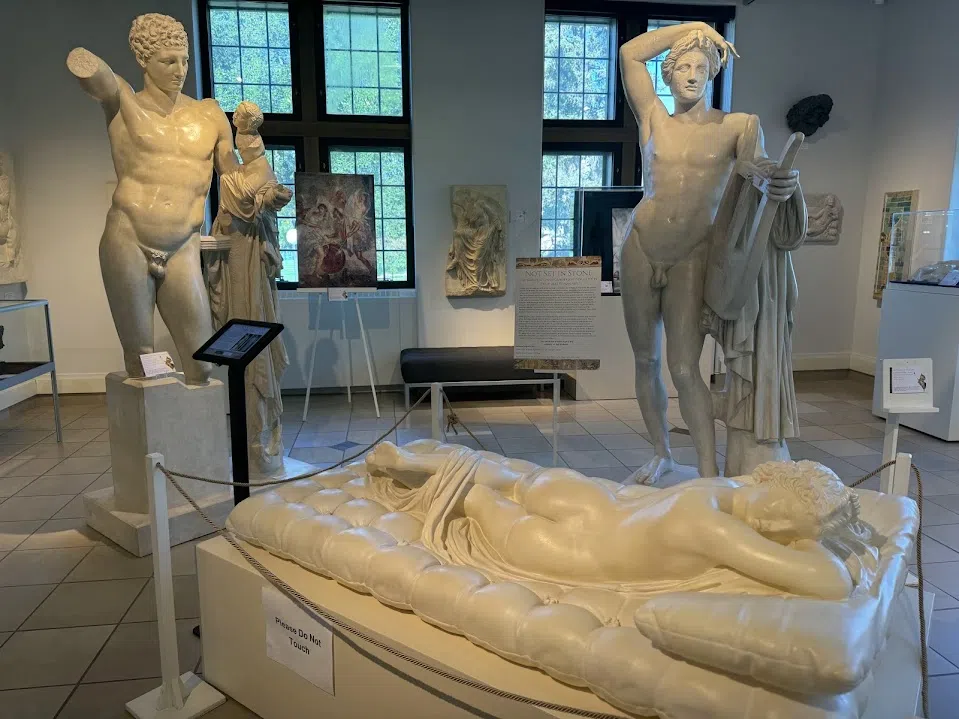

“I’m very fond of our Sleeping Hermaphroditus – that one that’s lying down,” said Harvey, pointing out a large sculpture depicting Hermaphroditus from Greek mythology.

“That’s actually our first full-scale 3D-printed statue that we got from the Louvre workshops a few years ago, so we’re pretty proud to have that as well in the collection.”

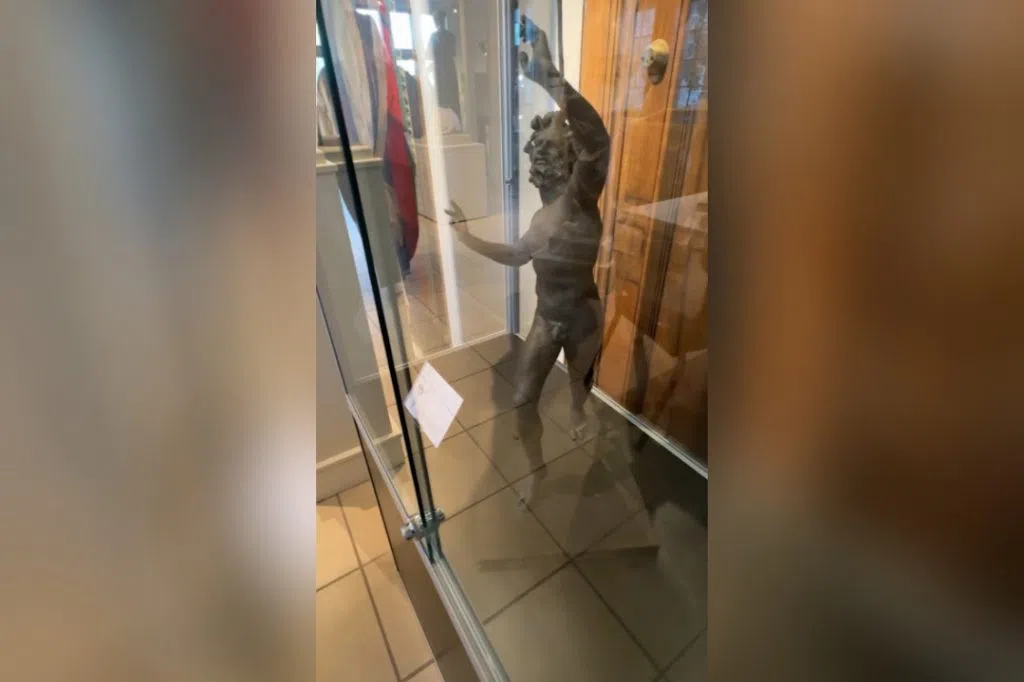

The Museum of Antiquities is also able to print its own 3D replicas on site, without having to import the pieces in from abroad.

“We dabbled a little bit ourselves. We have a smaller 3D-printed statue over there, a sculpture of the Dancing Fawn from the House of the Fawn in Pompeii,” Harvey recalled.

“We’ll scan first, print it in multiple parts, and then put together and paint it to look like the original.”

“We dabbled a little bit ourselves. We have a smaller 3D-printed statue over there, a sculpture of the Dancing Fawn from the House of the Fawn in Pompeii,” Harvey recalled. “We’ll scan first, print it in multiple parts, and then put together and paint it to look like the original.” (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

Harvey said the material is a type of resin that feels like plastic, and the replicas are often hollow.

“It’s done very well,” she said.

“You almost can’t tell the difference between the plaster cast and the 3D-printed one.”

How it works

The Museum of Antiquities operates within the University of Saskatchewan, but its not just for students and faculty to enjoy.

Members of the public can enjoy the ancient artwork without a pricey admission fee.

“My goal as director is to maintain the accessibility of this collection, free to whoever wants to come and see it,” Harvey said.

“Hopefully we’ll continue to get many visitors and supporters, as we have been over the years, and go for another 50 years after this one.”

For those whose plans do not include a pricey ticket to Europe to see the originals, Harvey said the museum is “their ticket to seeing these magnificent sculptures in the flesh.”

Members of the public can enjoy the ancient artwork, without a pricey admission. (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

A lot of the Museum’s educational programming is also free, although the Museum suggests a donation upon entry.

“We generally don’t charge anything, because we want people to come out and see this, and enjoy it without having to worry about the cost,” said Harvey.

The museum is hosting a “Medieval Times” event on Saturday, which will feature games, crafts, combat and historical artifact handling lessons, and the event is free for the whole family. Harvey said they expect about 1,000 people will come out to the university’s Bowl for the event.

The museum is located in room 106 in the Peter MacKinnon Building at the University of Saskatchewan, and is open to all Monday to Saturday.

The museum is located in room 106 in the Peter MacKinnon Building at the University of Saskatchewan, open to all Monday to Saturday. (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

The majority of the collection is donated. The University started the collection, and put forward funds to buy the first dozen statuses for the museum, which included the Venus to Milo and the Charioteer of Delphi. Since then, the collection has grown from a mere dozen to more than 150 pieces through donation.

“That’s a testament to the enthusiasm and interest in our local community for these ancient cultures,” Harvey said.

“We’re pretty excited that even after 50 years we’re still adding things to the collection thanks to the support of the community.”

A major milestone

Next year will mark 50 years for the Museum of Antiquities, and Harvey said they plan to mark the milestone in a big way.

“We’re acquiring several new casts for the collection to celebrate, so there’ll be a series of events celebrating the museum,” Harvey revealed.

“We’re gonna get the Law Code of Hammurabi, which is a big deal, and hopefully we’ll attract some law people into the museum to see the first law code.

The Code of Hammurabi is a Babylonian legal text, written during 1755–1750 BC. It is the longest, best-organized, and best-preserved legal text from the ancient Near East, and was purportedly written by Hammurabi, sixth king of the First Dynasty of Babylon.

“It’s a huge pillar. It’s about as tall as some of these other statues, and then it’s all Cuneiform writing on it, with this ancient Babylonian law code,” Harvey said.

The Code of Hammurabi is the longest, best-organized, and best-preserved legal text from the ancient Near East. (Louvre Museum website)

Stepping back in time

While the ancient world is thousands of years in the past, when you stand in the museum it feels more alive than ever.

Harvey said visitors are often surprised and shocked that such a collection can be found in Saskatchewan, and how many statues are on display in such a small space.

“We’re in the middle of Saskatchewan in the prairies, and to be able to have this opportunity to take a step back in time a couple thousand years and to see these statues in the flesh really is a great pleasure for a lot of people, and a great surprise.”