Heading down the elevator shaft of Nutrien’s potash mine near Rocanville, you are immediately hit with hot air and the smell and taste of salt.

Surprisingly, the ride down was very smooth, minus the constant popping of my ears. It only took a couple of minutes to arrive in the mine.

Gillian thought the mine would feel cramped and claustrophobic.

But little did we know the mine is about the size of Calgary, Alberta.

Listen to Massie and Garn explain what it is like below the earth on Behind the Headlines:

The mine is so big that of the 250 employees working underground that day, we saw no more than 10.

Chris Machinak, a 22-year mining veteran, said this is typical.

“In a day you probably put on anywhere to 100-150 kilometers just to see your people,” he said.

Chris Machinaik said that generations of his family have worked in the mines. He loves being able to work close to home in “his backyard.” (Nicole Garn/980 CJME)

There was no way we could walk where we needed to go during our two-hour tour.

To get around, we took a glorified nine-seater ATV called the “people mover” by staff. The half-hour ride was so smooth I nearly fell asleep.

With all the driving miners do, the same traffic laws apply beneath the earth like on the roads above ground.

There’s a speed limit of 40 kilometres per hour.

When Machinak drove by one of the speedometers he was clocked at 36 km/hr.

There’s even etiquette of turning off your high beams and replacing them with low beams when passing another driver.

The best mode of transportation in the mines is the “people mover.” It travels no more than 40 km/hr. (Nicole Garn/980 CJME)

We drove 16 km to get to the Tiger Miner.

The Tiger Miner machine gets its name from competitions put on by staff. They rotate through different animals.

“(We’ve done) bears, cats and birds of prey,” Machinak said.

None of his name suggestions have been chosen, he explained with a laugh.

The miner is a huge machine. It has four routers with teeth that spin in circles to break down the potash.

According to Machinak, the circular cutting style is the most efficient.

The potash comes off the wall pretty easily. Someone best described the look and texture as dragon scales.

From the miner, the potash is put onto belts. Machinak said it can take a few days to get the potash from the miner to the belt and then up to the surface where it goes through a milling process.

The area with the belt was very hot. It was around 35 C in there, whereas near the Tiger Miner, it was around 27 C.

This area was extremely salty. You could feel it on your skin and taste it when you licked your lips.

Potash rained down from the sky kind of like snow. It covered the “mine limo” as Gillian liked to call it, and our equipment with potash dust.

The “mine limo” covered in potash dust after a trip down to the belts that move the potash around the mine. (Nicole Garn/980 CJME)

My backpack is still covered. It serves as a reminder of our trip down to the mine.

Once the potash has been processed, it mainly serves as fertilizer which helps get food on the table.

Something that blew Gillian’s mind is that our pink-coloured potash is dyed red to serve Asian markets. For Asian countries, the colour white is typically used during times of mourning, while the colour red symbolizes success and happiness.

My favourite part of the mine was all the hints of personality.

On the potash dust-covered walls there were messages of pride, inside jokes and games of tic-tac-toe.

Things like speedometers, Wi-Fi, fancy porta potties, vending machines with equipment and iPads to log one’s process were also things I didn’t expect to find below the earth.

Vending machines are filled with equipment for miners in case they forgot something. (Nicole Garn/980 CJME)

Another key point of functionality in the mines is making sure the air is breathable.

Training manager Calvin Petracek said huge fans blowing air are essential to meet air quality measures.

“If those fans shut off on service, we shut down underground,” he said.

Calvin Petracek said that safety is a top priority at Nutrien’s potash mine near Rocanville. (Nicole Garn/980 CJME)

On our way to the Tiger Mine, we probably passed through around six air lock chambers. He said the chambers help move air through the mine.

“Our workers have decent air, safe air to continue on with their days,” Petracek said.

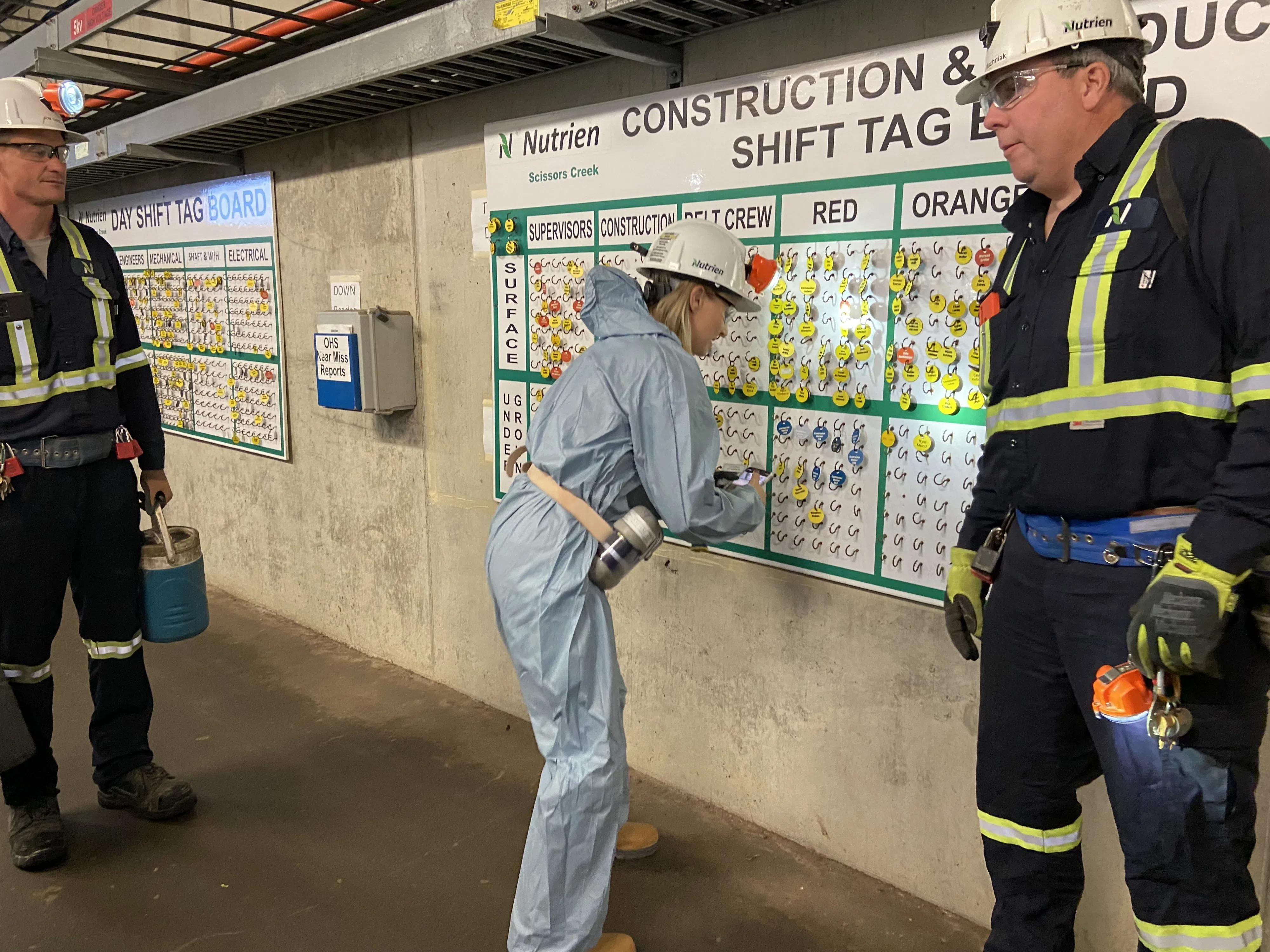

When we were back on solid ground, it was time to collect our visitor tags — each one on the wall represents a worker down below.

We also had to “clock in” and “clock out” of the mines. My scanner had trouble on the way out, it’s like the mine didn’t want me to leave.

The mine uses a tag system to keep tabs of who’s down below. For every tag on the wall, it means one person in the mine. (Nicole Garn/980 CJME)

After the quick two-hour mine tour and a tour of the milling facility, Gillian and I were back on the bus headed home to Regina.

Six different stories later, a souvenir filled with potash and a newfound appreciation for the mines, I’d call it a successful day.

Gillian Massie (left) and Nicole Garn pose for a photo in the elevator shaft of the mine. (Nicole Garn/980 CJME)

-with files from 980 CJME’s Gillian Massie