Beneath one of the dozens of vintage Christmas displays at Saskatoon’s Western Development Museum, Randall Simpson is tinkering away at one of the motors, powering tiny figures that delight audiences each holiday season.

“I’m the only person doing the maintenance here, and it’s kind of hard to find somebody who’s got the mechanical aptitude and is willing to lay on the floor and get greasy,” said Simpson.

Randall Simpson works hard to keep the mechanized displays from the 1940s in working condition. (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

Simpson has been volunteering at the museum for the past four years, ever since the COVID-19 pandemic.

“My wife had volunteered at the museum with the Women’s Auxiliary, and she dragged me along. And then I got tapped by the volunteer co-ordinator. It’s like ‘Hey, you’re kind of a handy guy. Do you want to work on Eatons?’” explained Simpson.

A vintage tradition

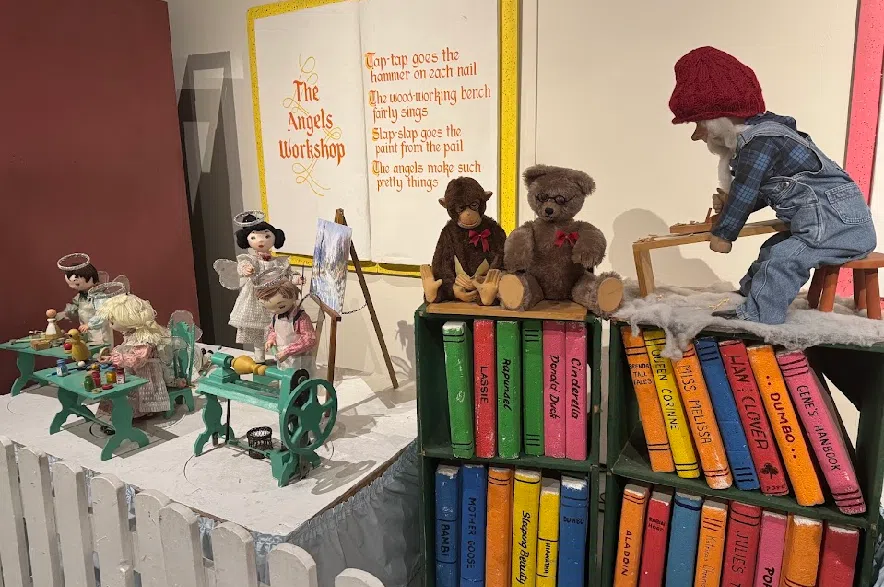

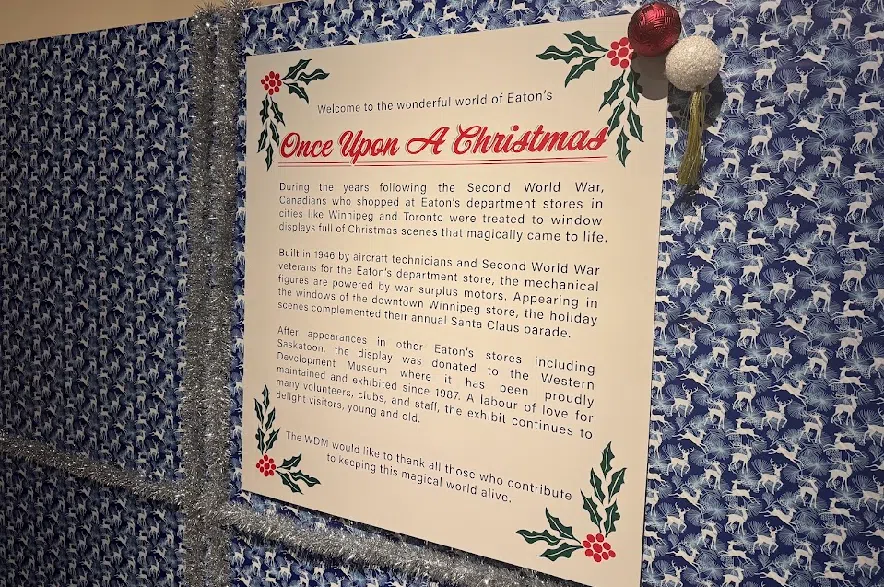

The Eaton’s “Once Upon a Christmas” display was built in 1948, originally crafted by the Canadian Air Force using spare parts left over from the Second World War.

But at a glance, you wouldn’t realize that below the surface the displays are powered by what were once tools of war.

“The big animals in the menagerie have got the motors in the base, and they’re running cables up through their legs, into their body, into the back of their head to make their eyes flutter. And that kind of a technology would have been used for control surfaces on airplanes,” Simpson explained from beside a large, furry giraffe.

Read More:

- Garden Talk: Christmas trees selling fast in Saskatchewan

- Watch: Museum of Antiquities tours the ancient world

- 60 years, 2 cards: The timeless Christmas tradition turned biography

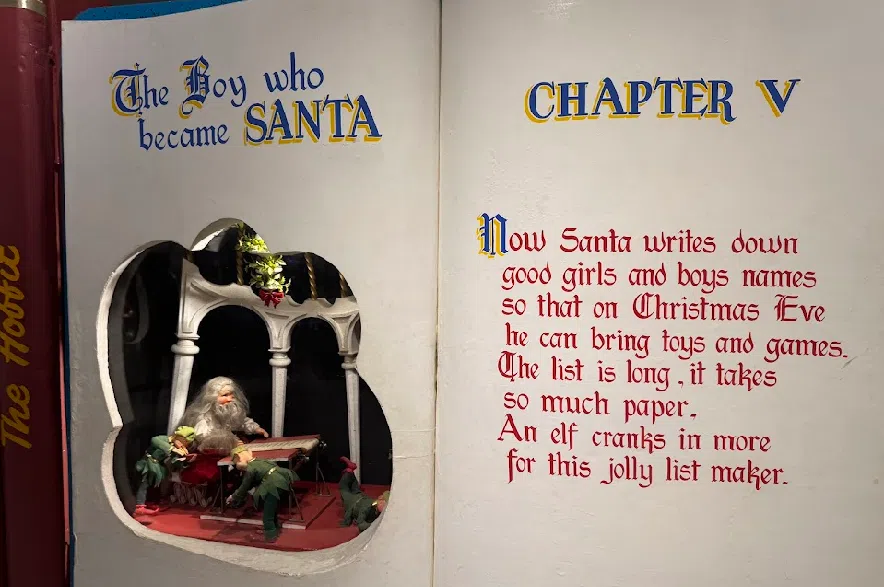

The Christmas displays that show Santa’s story as he grows from a boy to a man were built for the Eaton’s store in Winnipeg.

In 1977, the Eaton’s location in Saskatoon purchased some of the units, displaying them in Midtown Plaza until the mid ‘80s.

Finally, in 1987, the displays came to the museum in Saskatoon, where staff and volunteers racked up nearly 3,000 hours mending, painting and repairing them in the first year alone.

Some of the displays were built using parts left over from the Second World War. (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

Many of the motors had stopped working, and mechanical systems had broken down. Electrical wiring needed replacing, along with broken figures and soiled scenery.

“I’m standing on the shoulders of giants. Like, I really haven’t done a lot to this,” Simpson said. “I’m keeping it running. The people that built this originally and did the major innovation, they’re the ones that really are the heroes.”

Volunteering venture

Simpson doesn’t have a mechanical background, or even one in technology. He worked for the provincial government before retiring early.

He credits his childhood for his ability to tinker with mechanics and make them work again.

Randall Simpson says he has no formal mechanical training, but picked up a lot of skills during the years he spent working alongside his father. (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

“My father was born on the farm so I just became, as a result of that, dragged along into all the mechanical things. He had rental houses, and so I was dragged along to help fix all that. It’s just something I really enjoy. I’ve got no formal training whatsoever,” admitted Simpson.

“Working on this is not rocket science. It’s just the idea of the more mechanical-type of things you do, the more you realize you can do.”

Magical mascot

Simpson’s passion project is a display in the spotlight near the entrance, which features a furry mechanical bear with a turning head and blinking eyes, known as “Punkinhead.”

“Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer was actually a creation of the Montgomery Ward company in the states, as a mascot to drive sales. Eaton’s in Canada goes, ‘Wow, what a great idea. We’ve got to come up with our own mascot,’” recalled Simpson.

“They contacted the guy who created Bugs Bunny, and he came up with this character.”

That man was Canadian cartoonist Charles Thorson, best known for designing an early version of the then yet unnamed Bugs Bunny.

He created “Punkinhead,” who appeared in several children’s books and in Eaton’s catalogues for many years.

Punkinhead originates in the story “Punkinhead: The Sad Little Bear.” Unlike the other bears, he had a large tuft of blond hair on the top of his head, and was ostracized, leading to being called “Punkinhead.”

In the story, Punkinhead was able to help Santa by appearing by his side at the Christmas parade and being able to wear a special hat due to his tuft of hair.

The bear became an important part of the Santa Claus Parade in 1948, and was a regular feature thereafter.

“It’s very, very very similar story. He’s got an issue with the goofy hair, and everyone makes fun of him because of his hair, but it eventually becomes his championing thing, like Rudolph’s red nose,” said Simpson.

“I’ve had him brought around the corner here into his own special little spot, but he’s still not getting the credit he deserves.”

Winter home

Simpson spends the summer months travelling with his wife in his retirement, but said the big work at the museum comes during the fall months.

“I show up here in October, the last couple years, (to) help get this thing running. And this runs until the beginning of January, and then when it’s down I come in a couple days a week and help the exhibits technician,” Simpson explained.

The Western Development Museum’s vintage Christmas displays are maintained by a pair of volunteers, including Randall Simpson. (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

“It’s something that I enjoy. It gets me out of the house every day. When this is running properly, that makes me happy, and just the behind-the-scenes aspect, watching people’s enjoyment of it is pretty neat. Like some of the kids are just fascinated.”

The mechanisms in the display originate from the 1940s, but Simpson said he wants to keep the original pieces working as long as he can.

“There’s no magic in here. There’s no actuators or computerization or high tech. This is all done with levers and belts and chains,” he said, pointing to one of the displays.

“I personally want to maintain the old-style mechanics of it as long as possible. You can go to pneumatics and much newer technology, still leaving the display portion looking like it does, but I do enjoy the levers and the grease and the noise and the clunking.”

The public can check out the Christmas displays at the museum until January 3. (Alex Brown/650 CKOM)

Simpson says he is one of two people assigned to the displays’ restoration and repair, but he said there’s always room for more volunteers at the Western Development Museum.

“There was a big drop-off during COVID, but the museum as a whole can use more volunteers. It’s just a matter of getting going again,” Simpson mused.

The “Once Upon a Christmas” display is open at the museum Saskatoon until January 3, and is included with museum admission.