It’s been five years since COVID-19 first arrived in Saskatchewan.

The first case was publicly reported March 12, 2020 in a person who had arrived back in Saskatchewan from Egypt. What followed were thousands more cases, many deaths, and a back-and-forth series of public health mandates.

Read More:

- Regina doctor suspended for prescribing Ivermectin for COVID

- World Health Organization declared COVID-19 pandemic five years ago today

- ‘How did we survive?’ What Canadians recall — and don’t — about the COVID-19 pandemic

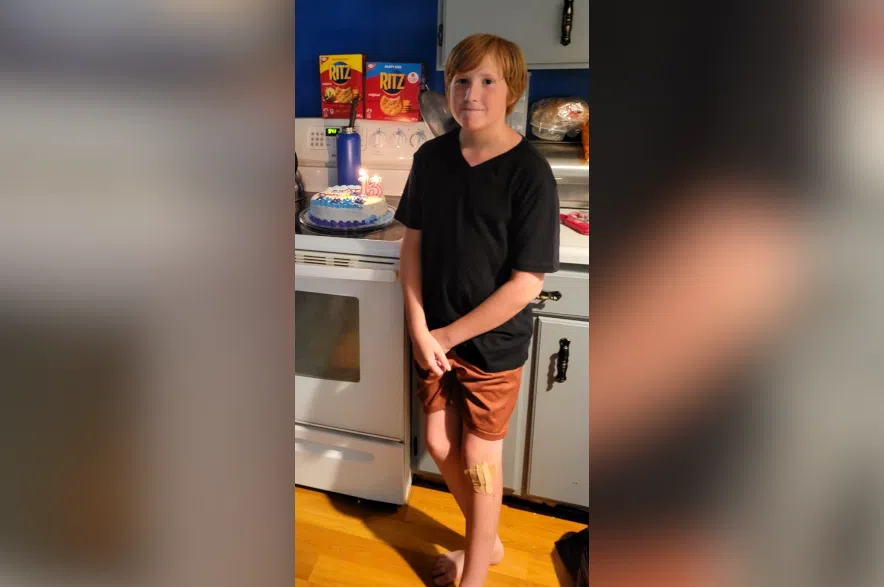

For many around the province, the pandemic feels like a lifetime behind them, but for others the effects linger, and they’re still battling them. People like Pam Milos and her youngest son, Ian.

Milos said it was a year into the pandemic that she and her whole family got COVID-19. She said Ian, then 10 years old, barely had any symptoms. But seven months later, in October of 2021, Ian started to complain of chest pain, which was getting worse.

“He was crying all night. He couldn’t sleep. He couldn’t move. He was in agony,” she explained.

Milos said they took the boy to the hospital and doctors had some ideas, but she said the treatments didn’t help.

A few weeks later, when they were in hospital for a different reason, a doctor saw Ian’s previous chart and gave Pam the first indication of what she would chase for the next year.

“She looked at me and she goes, ‘Your child has long COVID.’”

What is long COVID?

Long COVID, also called long-haul COVID, and post acute qequelae of COVID-19 in clinical settings, covers a wide basket of symptoms and still doesn’t have a universal definition.

It’s a long-lasting, usually chronic condition that can start anywhere from weeks to months after a COVID infection, according to information from the Saskatchewan Health Authority and the Mayo Clinic in the U.S.

The symptoms vary widely in severity. They can come and go, and can range from exhaustion and “brain fog,” to digestive problems and almost everything in between.

The severity of long COVID symptoms doesn’t seem to correlate with the severity of a person’s sickness during their original infection, and it’s still not entirely clear why some people develop long COVID, though researchers have been kicking around some ideas.

One study on long COVID, published by VIDO at the University of Saskatchewan in 2024, found that as many as 30 per cent of people may develop long COVID. The results suggest those who develop long COVID may have had a “sub-optimal” response to the original infection by antibodies, and may also be more susceptible to subsequent infections.

Confusion and frustration

Even though one doctor seemed to identify the problem quickly, Milos still had a battle ahead of her with Ian’s pediatrician, who dismissed the idea, telling her there was no such thing as long COVID.

Milos said the chest pain went away as quickly as it had started, but then Ian began getting migraines. She said they would be so bad that he would stand shaking from the pain, and couldn’t get more than an hour or two of sleep a night.

“You’re not supposed to give them adult doses until they’re 12, but children’s Advil wasn’t touching it and no one would give us anything for the pain,” said Milos.

At this point, she said doctors were telling her Ian was faking it, that it was anxiety, or that he was just looking for attention.

A couple of months after that, Milos said her son developed a debilitating exhaustion, sleeping almost 18 hours a day.

“There were a few times we tried to wake him up that we couldn’t wake him up. The first few times it happened, my husband and I are shaking him, calling him, pulling blankets. We’re physically moving him and he’s not waking up,” she said.

Milos said she knows teenagers are tired and need more sleep than adults, but said Ian had always been out the door and active before. Doctors told her he was just being lazy.

“I’m like ‘No, this isn’t my kid. There’s something wrong, there’s something really, really wrong with this kid,’” said Milos.

The illness caused problems at school, too. At that time, Ian was attending school virtually, but Milos said he just couldn’t stay awake, and she would get calls from teachers saying that he wasn’t on camera.

Milos persisted, taking Ian to a new pediatrician and insisting on rounds of testing. Eventually, a year after symptoms first started, they got the official diagnosis of long COVID, though Milos said the process was like a nightmare.

They had to wait months to get Ian into a clinic which specialized in long COVID in Regina, largely because it had so many patients. Ian has been working on it and getting better, but Milos said he missed nearly a year of school over two years because of the problems.

And while Ian got better, his mother didn’t.

Pam’s problems

During the entire ordeal, Milos herself had been dealing with brain problems, and was having trouble remembering things and concentrating.

“My brain’s getting worse and I’m just attributing it to the stress of not being able to help my child (and) nobody listening to us,” said Milos.

Once Ian started to improve and the stress cleared up, her problems persisted. She said she worried it was something like early onset dementia.

“I used to be an avid reader. Had an incredible memory, used to have a photographic memory, and (now) I’d ask somebody something, I’d turn around, and the whole conversation would be gone,” she explained.

Her day-to-day functions, like work, she could deal with, but she couldn’t concentrate enough to take a course and get more certifications, or even read a book. She said she hadn’t been able to read a book in three years prior to this winter.

Milos said she also had no interest in hobbies she’d previously loved and been really good at, like crocheting, quilting and scrapbooking.

“It almost feels like taking away my memory and my brain power has taken away some of my identity,” she said.

Last summer, she also got a diagnosis of long COVID, and got on a list for treatment at the same clinic as her son. She also started trying medication.

“I’m not quite as fuzzy anymore. I’ve had more moments of clarity in the last month from some of the meds,” said Milos.

She said she also had some smell and taste issues, but now those have started to resolve as well.

Milos said her son is at about 70 per cent of his normal capacity now. This past school year, he attended more classes than he missed for the first time since 2021. She said he’s still working hard on the symptoms, but he’s alright with where he’s at. Milos said she’s at about 65 per cent herself, but she’s still working hard to improve.

“I’m determined to fix my brain, because I am not ready to go ‘This is my new normal of no memory.’ I can’t accept that,” she said.

Milos said she knows at the back of her brain that this is a chronic illness and it could take years to get back to normal, but she also knows it might never happen.