In the third chapter of Klara Belkin’s extraordinary journey, we follow her out of the ashes of war and through the struggle of rebuilding her life in a world forever altered.

After surviving the horrors of Bergen-Belsen and the upheaval of post-war Hungary, Klara’s path led to a daring escape — a journey that would take her from Budapest to Vienna, and ultimately to Canada.

Her life would flourish in ways she never could have imagined — becoming a celebrated cellist, a professor and a mother.

But despite the years of success and happiness, Klara hasn’t forgotten the past that shaped her.

Klara’s story is not just one of survival; it’s a story of remembrance and resilience, a call to ensure that we never forget the lessons of history.

Listen to Episode 3:

Listen to Episode 2:

Listen to Episode 1:

The cello she brought with her from Hungary is long gone. But this dress — painstakingly handmade by Klara Belkin’s grandmother — remains. It is the only tangible connection to her life in Hungary. The only item left that links her to the past, to the home she once knew. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Transcript of Episode 3:

In her Saskatoon apartment, Klara Belkin flings open her closet door, reaches in, and pulls out one of her most precious possessions. A deep blue velvet dress.

This dress — painstakingly handmade by her grandmother — is the only tangible connection to her life in Hungary.

A quiet pride fills her eyes as she holds it in her hands.

After a long pause, she carefully places it back in the closet, her fingers lingering on the decades-old fabric for just a moment longer before continuing on with her story.

Klara: “The Americans offered us to take to the west, not to go back. But everybody wanted to go back, because everybody wanted to see their family. So they went back to Hungary. Behind the Iron Curtain. How do you say it? From… There is the expression to jump from one into the same hot heat…”

As the saying goes, ‘From the frying pan into the fire.’

Klara’s return to Hungary after the war wasn’t the homecoming she had imagined.

Back in Szeged, it was clear that the world around her had changed.

Klara: “And so we went home and we didn’t have a nice welcome. Was not a nice welcome. Of course not. Because whoever had the chance took over our homes, and we never got back. Nobody did. My grandma and me and my mom, we went to downtown in a room. That’s how we started. Then we were really sorry that we didn’t go with the Americans to west. I couldn’t go back to school. I went back to school for a couple of days, and I said, I can’t do it. I couldn’t look at kids and normal life. It was just… I said, ‘I don’t belong here.'”

It wasn’t long before they moved to Budapest in search of a fresh start.

And while life would never be the same as it was before the war, Klara was able to find moments of pure joy as the years went by.

Klara: “I was visiting in a small, little town in the summer, so I was practicing outside in the garden. And they had all kinds of animals there, like chickens, ducks and pigs. And that little pig, he was watching and listening. And so I tried different pieces. He loved classic more than romantic, and I could tell, because his ears went up. And when I started to play romantic, his ears went down. Why are you laughing? That’s true! Why are you giggling?”

Klara Belkin reflected on a moment of unexpected joy after the war, recalling a summer in a small town where she played music outside. A curious pig, captivated by her performance, responded to different pieces, its ears perking up for classical music and drooping for romantic tunes. “It’s true!” she laughed, sharing a cherished photo of the pig, ears alert, in the garden. (Submitted)

In the autumn of 1956, a revolution began to take root in Budapest.

University students fed up with Soviet oppression rose up, and the city became a battleground.

As the streets ran crimson with blood, Hungarians began to flee.

Klara: “When the Hungarians started to run out and the border was sort of open. My mom said, you have to go. Got my cello. And I went.”

To bring along a cello seems almost absurd in this context. It was large, unwieldy, and impractical for an escape from an oppressive regime. But for Klara, it was more than just an instrument.

Klara: “I spent my life doing this cello, and that was my profession. See, I got a degree of performer and professor. I spent 10 damn years in a university.”

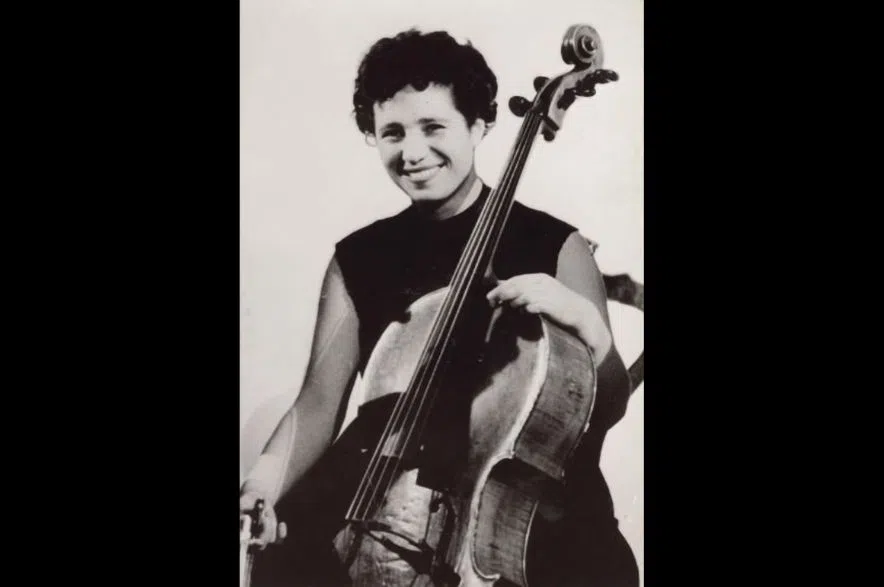

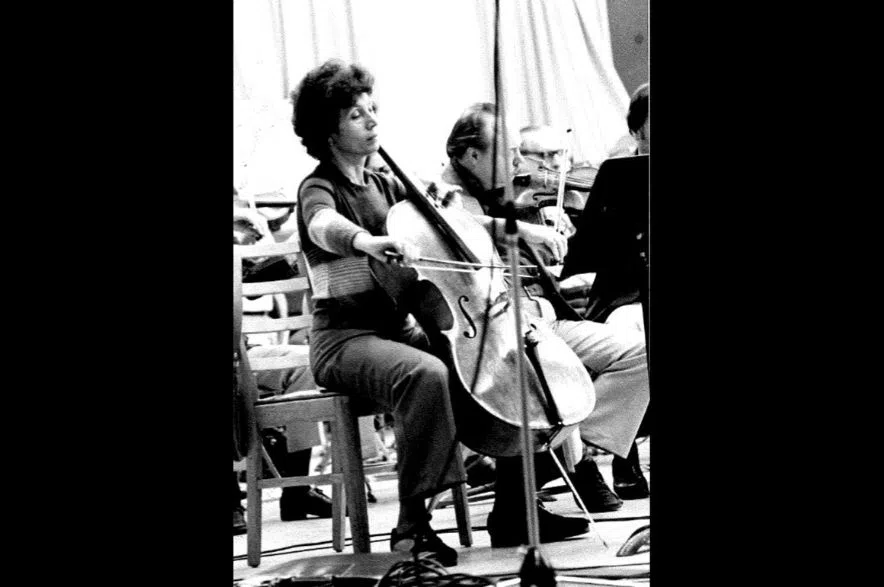

After liberation Klara attended the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest, a prestigious music conservatory. She studied cello, completing two degrees. (Submitted)

With the help of a smuggler, paid with a handful of family jewelry, Klara fled from Hungary.

Klara: “Got on an ordinary train in Budapest to the last station before the border. We got out there with this old man, and then he had a soldier, the army guy. The army guy, was carrying my cello because it was heavy, you know. We walked about, I don’t know, a couple of miles. So that’s how I got through. It was fun. You know, when you’re young, it’s something so different. And I was what, 26 or something. Somehow, I don’t remember how I got to Vienna, but I got to Vienna with my cello. So, where can we go? Go to Canada. I said ‘Yeah, we can go! Where is Canada?'”

Klara couldn’t even pick out Canada on a map at the time, but she agreed to make it her new home.

Klara: “We had to go to the Canadian Embassy in Vienna to meet the ambassador Canadian guy. I was single, and so they asked me if I know how to cook, and I said, ‘No. But I can play the cello!’ But they said that’s not what they need in Canada. He said ‘It’s a very new country. They need builders, like electricians and, you know, tradesmen. He said ‘It’s a new country. They don’t need that culture thing there.’ I said ,’Oh, they don’t have? We’ll bring it! you know. And I said going, we’re going to Canada. So we did. And of course, I ended up being the principal cellist for the Winnipeg Symphony and Professor of Music in the U of M. So he was wrong.”

Klara Belkin was the principal cellist with the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra and the Canadian Broadcasting Orchestra for many years. She toured extensively and later became a professor at the University of Manitoba’s School of Music. (Submitted)

Klara’s life in Canada flourished. She married, had two daughters and built a career that many would envy.

She became a respected musician, both as a performer and a professor of music, and spent 60 years in Winnipeg before moving to Saskatchewan two years ago.

Klara Belkin married her husband, Emile Belkin, in 1960. She said she didn’t speak a word of English when they first met, and he didn’t speak Hungarian. Regardless, the two fell in love. They were married for 60 years before Emile’s death in 2020. (Submitted)

Klara Belkin, proud of her esteemed career, holds an even deeper pride for her daughters, Brenda and Lisa. She considers this her favorite photo, as it captures a moment of pure joy — holding her babies. (Submitted)

Klara Belkin lived in the Szeged ghetto. She survived Bergen-Belsen. Witnessed the blood-soaked streets of Budapest during the Hungarian Revolution.

Remarkably, she isn’t the kind of person who wants to erase those memories.

She wants to remember. And she wants us to remember, too.

Klara: “History repeats itself. It seems it does, you know. Because it seems… it seems that humans never learn.“

In Saskatoon, I’m Brittany Caffet.