The CEO of Boeing defended the company’s safety record and declined to take any more than partial blame for two deadly crashes of its bestselling plane even while saying Monday that the company has nearly finished an update that “will make the airplane even safer.”

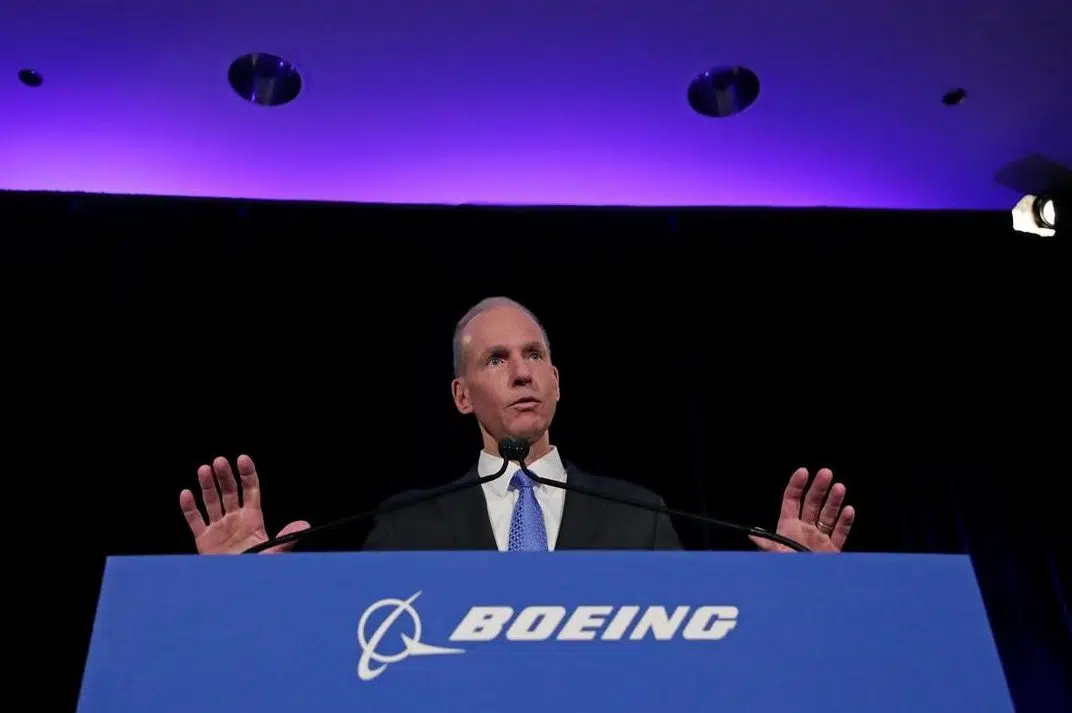

Chairman and CEO Dennis Muilenburg took reporters’ questions for the first time since accidents involving the Boeing 737 Max in Indonesia and Ethiopia killed 346 people and plunged Boeing into its deepest crisis in years.

Muilenburg said that Boeing followed the same design and certification process it has always used to build safe planes, and he denied that the Max was rushed to market.

“As in most accidents, there are a chain of events that occurred,” he said, referring to the Lion Air crash on Oct. 29 and the March 10 crash of an Ethiopian Airlines Max. “It’s not correct to attribute that to any single item.”

The CEO said Boeing provided steps that should be taken in response to problems like those encountered by pilots of the planes that crashed. “In some cases those procedures were not completely followed,” he said.

The news conference, held after Boeing’s annual meeting in Chicago, came as new questions have arisen around the Max, which has been grounded worldwide since mid-March.

Southwest Airlines said over the weekend that Boeing did not disclose that a feature on the 737 — an indicator to warn pilots about the kind of sensor failures that occurred in both accidents — was turned off on the Max. Southwest said it found out only after the first crash of the Lion Air Max. Boeing said the feature only worked if airlines bought a related one that’s optional, and in any case the plane could fly safely without it.

Separately, published reports said that federal regulators and congressional investigators are examining safety allegations relating to the Max that were raised by about a dozen purported whistleblowers.

The Boeing event occurred on the same day that the Federal Aviation Administration convened a week-long meeting in Seattle of aviation regulators from around the world to review the FAA’s certification of MCAS, a key flight-control system on the Max.

A spokesman said the FAA will share its technical knowledge with other regulators, but their approval is not needed before the plane resumes flying in the U.S.

Boeing has conceded that in both accidents, MCAS was triggered by faulty readings from a single sensor and pushed the planes’ noses down. Pilots were unable to control the planes although the Ethiopian Airlines crew followed some of the steps that Boeing recommended to recover.

Muilenburg told shareholders that Boeing is close to completing an upgrade to flight software on the Max “that will ensure accidents like these never happen again.”

In the brief news conference that followed, Muilenburg took six questions from reporters, including whether he will resign — he has no intention of doing that — and left as reporters persisted, including one who pointed to the deaths of 346 people and urged the CEO to take more questions.

Besides the software update, Boeing will present the FAA with a plan for training pilots on changes to MCAS. The company is pushing for training that can be done on tablet computers and, if airlines want to offer it, additional time in flight simulators when pilots are due for periodic retraining.

A requirement for training in simulators would further delay the return of the Max because of relatively small number of flight simulators.

The union for American Airlines pilots wants mandatory additional training including, at a minimum, video demonstrations showing pilots how to respond to failures of systems on the plane. Dennis Tajer, a 737 pilot and union spokesman, said Boeing and the FAA must require more training rather than leaving the option to airlines.

“Not every pilot that goes out there and flies is a Boeing test pilot,” Tajer said. “If something happens anywhere in the world, it affects all of us.”

During the one-hour annual meeting, shareholders elected all 13 company-backed board nominees, including newcomer Nikki Haley, the former South Carolina governor who lobbied for a Boeing plant there, and former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations.

Several shareholder resolutions were defeated, including one to name an independent chairman whenever possible instead of letting the CEO hold both jobs. It got 34% support.

A chairman-CEO “is not always a bad thing, but at times of crisis it’s hardly ever a good idea,” said Matt Brubaker, CEO of business-strategy consultant FMG Leading, who was not involved in the debate. “The place they are in now, they need the scrutiny of an inwardly focused CEO to drive change.”

Muilenburg opened Monday’s meeting with a moment of silence for victims of the two crashes. Later that day, lawyers for two Canadian families who lost relatives in the Ethiopian Airlines crash filed the latest in a growing number of lawsuits against Boeing, claiming the plane maker was negligent about safety.

Hiral Vaidya, whose in-laws and four other family members died in the crash, said there were no remains left to cremate.

“We have no closure, we have no peace, we have no answer,” she said, fighting back tears.

___

David Koenig can be reached at http://twitter.com/airlinewriter

David Koenig, The Associated Press