VANCOUVER —Japanese Canadians across the country are meeting to discuss how an apology by the British Columbia government could be backed by meaningful action for those who were placed in internment camps or forced into labour because of racist policies during the Second World War.

The federal government apologized in 1988 for its racism against “enemy aliens” after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941 but the president of the National Association of Japanese Canadians said British Columbia’s apology in 2012 did not involve the community.

Lorene Oikawa said the association is working with the provincial government to consider how it could follow up on the apology to redress racism. The majority of about 22,000 interned Japanese Canadians lived in B.C. before many were forced to move east of the Rockies or to Japan, even if they were born in Canada.

“We weren’t informed about the apology so it was a surprise to us,” Oikawa said about B.C.’s statement, which, unlike with the federal government’s apology, did not go further to resolve outstanding historic wrongs that saw families separated and property and belongings sold.

“We accepted the apology but we just want to have that follow-up piece that was missing so that is what the current B.C. government has agreed to and started with this process of having community consultations,” she said of the redress initiative funded by the province.

Consultations began in May and by the end of July will have been concluded in Toronto, Hamilton, Winnipeg, Calgary, Edmonton, Vancouver and seven other communities in British Columbia. Online consultations are also being conducted before recommendations will be forwarded to the province this fall.

So far, some participants have asked that school curricula include racism against Japanese Canadians as well as initiatives to educate the general public about the intergenerational trauma that families have experienced, Oikawa said.

Lisa Beare, British Columbia’s minister of culture, said the government is supporting the association as it holds consultations so community members can offer recommendations for legacy initiatives.

“We recognize that significant harm came to Japanese Canadians as a result of provincial government actions during the Second World War,” she said in a statement. “Japanese Canadians became targets simply for their identity, and in many cases lost personal property, jobs and homes.”

Addie Kobaishi, 86, was born and raised in Vancouver but her family had to leave their home when they were relocated to the Tashme internment camp, the largest in Canada, near Hope, B.C.

She said her grandmother and aunt ended up in a holding area at Hastings Park in Vancouver before they too were sent to Tashme, where residents faced brutally cold winters and had no indoor toilets or water as part of what was a “confusing” year and a half for her, starting at age 10.

“The conditions were harsh, the housing was harsh,” she said from a Scarborough, Ont., nursing home where she attended consultations about B.C. redress. Kobaishi said her family settled in Montreal because of the discrimination they faced in Toronto, where they wanted to live, though she moved there in the late 1970s.

Being interned and doing difficult farm labour changed many people’s lives forever, she said, noting her father died at 47 and never did go back to B.C.

“My uncle said to me many, many years later that it spoiled his life. He did marry, he had two children, but he did end up an alcoholic,” she said of Koazi Fujikawa, who had been sent to Yukon during the war as part of a crew constructing the Alaska Highway.

Kobaishi called on the B.C. government to accompany its 2012 apology with substantial and ongoing education as part of the school curriculum to teach students about policies that uprooted Canadian citizens.

“I do think they should be held responsible for something more than just an apology,” she said.

Her daughter, Lynn Kobaishi, president of the Toronto chapter of the National Association of Japanese Canadians, said during the war politicians in B.C. lobbied the federal government to resort to racist policies.

“It was all driven by B.C. That disempowered and disenfranchised people and allowed what happened to happen,” she said.

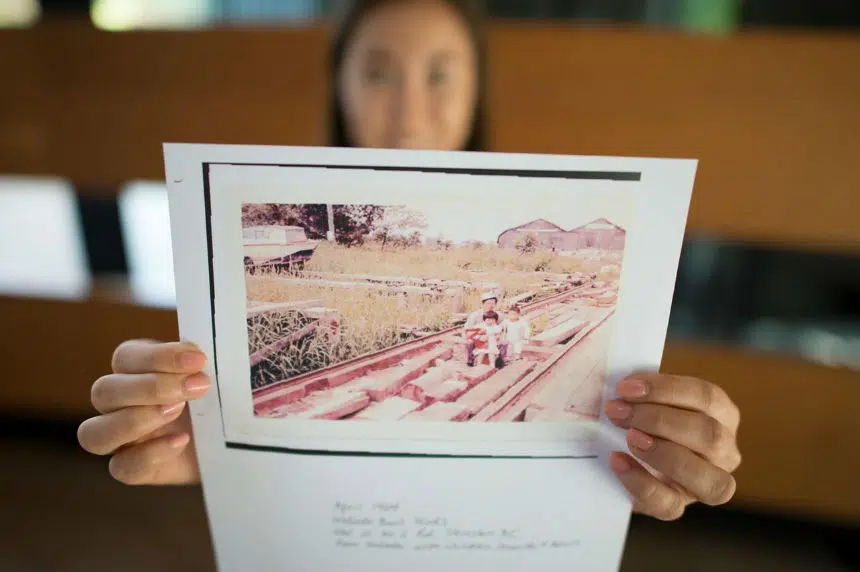

Ryanne Macdonald, 21, a fourth-generation Canadian of Japanese descent, is trying to unravel her family’s history with some clues from her reluctant grandmother’s stories.

She said her grandfather, Ryan Nakade, was 13 when his family’s boat business was confiscated by the government and he was forced to labour at a farm in Grand Forks, B.C., over 500 kilometres from his home in Richmond.

“My grandfather passed away before I was born so I never got to hear the story from him,” said MacDonald, who is currently doing a summer internship at the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre in Burnaby, where she’s working as an archival assistant.

“Since I started working there my grandma started talking about her experiences more, which is something she never opened up about before just because she tends to want to talk about it only with other people who’ve been through the same experience as her because they can relate,” Macdonald said.

She said she wants to be able to understand what her grandparents went through so those actions can’t be repeated.

“I think it was terrible and it was unfounded fear that they were going off of because they were treating the Japanese Canadians like they weren’t citizens. Both my grandparents, they were born in Canada.”

Macdonald said she learned about racism against Japanese Canadians in a Grade 10 social studies class but the content was “glossed over and it didn’t seem as bad as it actually was.”

Camille Bains, The Canadian Press